Young Country : Aren't Country Singers Getting Younger These Days?

First Published Country Music International, March 1997

A new generation of genuine talent, or simply an army of photogenic pin-ups manipulated to part the young record-buying public from their cash? Alan Cackett examines the Teen Country phenomenon currently sweeping the Nashville skyline.

A new generation of genuine talent, or simply an army of photogenic pin-ups manipulated to part the young record-buying public from their cash? Alan Cackett examines the Teen Country phenomenon currently sweeping the Nashville skyline.

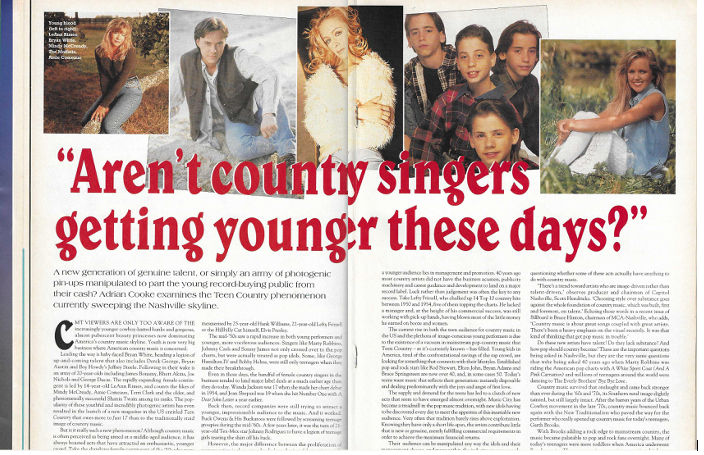

CMT viewers are only too aware of the increasingly younger cowboy-hatted hunks and gorgeous, almost pubescent beauty princesses now dominating America’s country music skyline. Youth is now very big business where America country music is concerned. Leading the way is baby-faced Bryan White, heading a legion of up-and-coming talent that also includes Derek George, Bryan Austin and Boy Howdy’s Jeffrey Steele. Following in their wake is an army of 20-year-olds including James Bonamy, Rhett Atkins, Joe Nichols and George Ducas. The rapidly expanding female contingent is led by 14-year-old LeAnn Rimes, and counts the likes of Mindy McCready, Amie Comeaux, Terri Clark and the older, and phenomenally successful Shania Twain among its ranks. The popularity of these youthful and incredibly photogenic artists has even resulted in the launch of a new magazine in the US entitled Teen Country that owes more to Just 17 than to the traditionally staid image of country music.

But is it really such a phenomenon? Although country music is often perceived as being aimed at middle-aged audience, it has always boasted acts that have attracted an enthusiastic, younger crowd. Take the shrieking female contingent of the 1950s who were mesmerised by 25-year-old Hank Williams, 22-year-old Lefty Frizzell or the Hillbilly Cat himself, Elvis Presley.

The mid-1950s saw a rapid increase in both young performers and younger, more vociferous audiences. Singers like Marty Robbins, Johnny Cash and Sonny James not only crossed over to the pop charts, but were actually treated as pop idols. Some, like George Hamilton IV and Bobby Helms, were still only teenagers when they made their breakthrough.

Even in those days, the handful of female country singers in the business tended to land major label deals at a much earlier age than they do today. Wanda Jackson was 17 when she made her chart debut in 1954, and Jean Shepard was 19 when she hit Number One with A Dear John Letter a year earlier.

Back then, record companies were still trying to attract a younger, impressionable audience to the music. And it worked. Buck Owens & his Buckaroo were followed by screaming teenage groupies during the mid-1960s. A few years later, it was the turn of 21-year-old Tex-Mex star Johnny Rodriguez to have a legion of teenage girls tearing the shirt off his back.

However, the major difference between the proliferation of younger artists in the past and today’s marketing of the music towards a younger audience lies in management and promotion. 40 years ago most country artists did not have the business acumen, publicity machinery and career guidance and development to land on a major record label. Luck rather than judgement was often the key to any success. Take Lefty Frizzell, who chalked up 14 Top 10 country hits between 1950 and 1954, five of them topping the charts. He lacked a manager and, at the height of his commercial success, was still working with pick-up brands, having blown most of the little money he earned on booze and women.

today’s marketing of the music towards a younger audience lies in management and promotion. 40 years ago most country artists did not have the business acumen, publicity machinery and career guidance and development to land on a major record label. Luck rather than judgement was often the key to any success. Take Lefty Frizzell, who chalked up 14 Top 10 country hits between 1950 and 1954, five of them topping the charts. He lacked a manager and, at the height of his commercial success, was still working with pick-up brands, having blown most of the little money he earned on booze and women.

The current rise in both the teen audience for country music in the US and the plethora of image-conscious young performers is due to the existence of a vacuum in mainstream pop-country music that Teen Country—as it’s currently known—has filled. Young kids in America, tired of confrontational ravings of the rap crowd, are looking for something that connects with their lifestyles. Established pop and rock stars like Rod Stewart, Elton John, Bryan Adams and Bruce Springsteen are now over 40, and in some cases 50. Today's teens want music that reflects their generation: instantly disposable and dealing predominantly with the joys and angst of first love.

The supply and demand for the teens has led to a clutch of new acts that seem to have emerged almost overnight. Music City has become a treadmill in the pop music tradition, with new idols having to be discovered every day to meet the appetites of this insatiable new audience. Very often that tradition barely rises above exploitation. Knowing they have only a short-life span, the artists contribute little that is new or genuine, merely fulfilling commercial requirements in order to achieve the maximum financial returns.

Their audience can be manipulated any way the idols and their management choose, and many within the industry are now openly questioning whether some of these acts actually have anything to do with country music.

“There’s a trend toward artists who are image-driven rather than talent-driven,” observes producer and chairman of Capitol Nashville, Scott Hendricks. “Choosing style over substance goes against the whole foundation of country music, which was built, first and foremost, on talent.” Echoing those words in a recent issue of Billboard is Bruce Hinton, chairman of MCA-Nashville, who adds, “Country music is about great songs coupled with great artists. There's been a heavy emphasis on the visual recently. It was that kind of thinking that got pop music in trouble.”

Do these new artists have talent? Do they lack substance? And how pop should countrybe come? These are the important questions being asked in Nashville, but they are the very same questions that were being asked 40 years ago when Marty Robbins was riding the American pop charts with A White Sport Coat (And A Pink Carnation) and millions of teenagers around the world were dancing to The Everly Brothers’ Bye Bye Love.

Country music survived that onslaught and came back stronger than ever during the 1960s and 1970s, its Southern rural image slightly tainted, but still largely intact. After the barren years of the Urban Cowboy movement in the later 1970s, country music bounced back again with the New Traditionalists who paved the way for the performer who really opened up country music for today’s teenagers, Garth Brooks.

With Brooks adding a rock edge to mainstream country, the music became palatable to pop and rock fans overnight. Many of today’s teenagers were mere toddlers when America underwent Brooksmania. They grew up in an environment in which country music was not only accepted, but was hip. It was at the height of this ready acceptance of country music that Billy Ray Cyrus broke through with Achy Breaky Heart, a country hit that teens could listen to without embarrassment.

Hordes of young fans followed Billy Ray everywhere he went, waiting for hours for the chance of a snapshot of their passing hero, or even the opportunity to touch him. At the time Cyrus presented himself as an object of adulation and drew some kind of strength from the response. Images of Elvis were evoked as Cyrus worked his young audience into a frenzy.

Yet Achy Breaky Heart wasn’t typical of Cyrus’s music, which has been as serious and heartfelt as that single was frivolous. Though he attracted armies of teens to his music, he was still on the wrong side of 30 to become a fully-fledged teen idol. Tim McGraw, however, was on the right side and, like Billy Ray, had a smash dance hit with the controversial Indian Outlaw a couple of years later.

McGraw was the one new artist who seized upon Garth Brooks’ country music vision, taking a blend of 1970s rock and mixing in just enough country to keep Nashville on his side. Unlike Billy Ray, he never got too serious, so records like I Like It, I Love It, lightweight and perfectly suited to the burgeoning country radio format, became perfect teen anthems,

The time was now ripe for youngsters to have their own idols, performers from their own world who understood the joy and pain of adolescence. Many of the new teen stars are rootless country performers who owe more to rock than trad country, and who have utilised musical elements from pop and rock rather than from the honky-tonk tradition. Typical is 23-year-old Bryan White, who is as well-groomed as a member of Ireland’s current teen sensations, Boyzone.

Born into a musical family in Lawton, Oklahoma, he started playing the drums at the age of five, switched to guitar at 17, and moved to Nashville after graduation. “It was pretty scary to make the move at the time,” he recalls. “But when you’re that young, you feel invincible.”

White’s savvy and fresh-faced, wide-eyed blend of country-pop was just right for the times, and within a couple of years of hitting Music Row he landed on Asylum Records. After hitting the number one spot with his third single, Someone Else’s Star, an appealing slice of confectionery country-pop, he was embraced by established Nashville stars who recognised that under the pop sheen there was a genuine talent. Something of a prolific songwriter, he co-wrote Sawyer Brown’s hit I Don’t Believe In Goodbye, as well as several songs on his first two albums.

These days, it’s not unusual to find hundreds of screaming teenage girls waving posters of White torn from 16 magazine and clamouring for his autograph, and much of his appeal comes from the way he deals with his young fans. He quickly endeared himself to the under-21 crowd adding afternoon shows to his itinerary to accommodate fans who were too young to see him at his evening shows. “I talked it over with my people about doing soundchecks in the afternoon and letting the fans come in and see the show when they’re not serving alcohol,” he explains.

White’s string of number one country hits and two platinum albums prompted the Nashville labels to rush out and sign any good-looking youngster they could find. They didn’t have to look much further than Music Row, which is where they found 24-year-old James Bonamy. The Florida kid was working as a demo singer when he was signed to Epic Records. Following in the White tradition, he topped the charts with his third single, I Don’t Think I Will, and is now firmly entrenched as a bona fide teen idol. Bonamy's stature is not built on hype, but the solid personality of a country boy who loves to sing. “What you see is what you get,” he declares. “I’m not reaching for fame by looking for something I'm not. I love making country music for its own merit, for being sincere and real.”

Another teen idol raised on a country music diet is Rhett Atkins. The 26-year-old Georgia boy was making a living as a songwriter and demo singer before landing his record deal three years ago. He charted his first number one record with That Ain’t My Truck, shared a stage with Reba McEntire and even appeared in a Julia Roberts’ movie, Something To Talk About. Atkins sings blue collar country tunes with an emotional edge, and A THOUSAND MEMORIES turned out to be a thoroughly satisfying debut album. “My main concern is for the quality of the music,” he says. “That always comes first for me.”

For every new teen hunk like Rick Trevino, George Ducas, Jeff Carson and Kenny Chesney, who have made that all important commercial breakthrough, there have been just as many like Andy Childs, Dude Mowrey, Wesley Dennis, Noah Gordon, Brett James and Woody Lee, who have not made it. Music Row is littered with young hopefuls, some of whom got as far as establishing record label development deals before being discarded.

If one group could lay claim to the title ‘youngest country’ it would have to be The Moffatts. Singer Scott was 12 and his triplet siblings Bob, Clint and Dave, were just 11 when they were signed to Polydor Records two years ago. They enjoyed a dance hit with Caterpillar Crawl and have become teen country pin-ups; Scott has already received one marriage proposal. However, poised on the brink of adolescence, their voices are soon set to change. “We’ll sing through it, though,” insists Scott. “Our voices will become deeper and it will be cool to have a different sound.”

Time will tell if these younger artists will go the distance. They certainly don’t exhibit the poise and maturity of newcomer LeAnn Rimes. More adult than child, this young woman is much more confident than the average 14-year-old. She moves with the air of a seasonal veteran and within a short period has made the transition from 13-year-old novelty act to a highly respected, mature-sounding singer, who carries much of country music’s hope for the future on her young shoulders. The leading question is, which of the teen-angel role models will she follow? The cool, self-control of Brenda Lee or the out-of-control raunch of Tanya Tucker? Whichever way it goes, LeAnn Rimes appears to have the talent and attitude to stick around for a long time.

Time will tell if these younger artists will go the distance. They certainly don’t exhibit the poise and maturity of newcomer LeAnn Rimes. More adult than child, this young woman is much more confident than the average 14-year-old. She moves with the air of a seasonal veteran and within a short period has made the transition from 13-year-old novelty act to a highly respected, mature-sounding singer, who carries much of country music’s hope for the future on her young shoulders. The leading question is, which of the teen-angel role models will she follow? The cool, self-control of Brenda Lee or the out-of-control raunch of Tanya Tucker? Whichever way it goes, LeAnn Rimes appears to have the talent and attitude to stick around for a long time.

The same applies to Mindy McCready. Sporting a fashionable belly button ring at 21, her initial hit, 10,000 Angels, sums up the dilemma facing so many young, single girls. Mindy left high school at 16 and worked part-time at her mother’s ambulance company before moving to Nashville, where she continues to play out the young girl role on songs like A Girl’s Gotta Do (What A Girl’s Gotta Do) and her chart-topping Guys Do It All The Time.

Even more impressive than Mindy as a teenage girl’s role model is Shania Twain, who has dared to take mainstream country music full gallop into the pop/rock hinterland. Though 10 years older, her slim figure, beauty queen looks and infectious, singalong numbers have made her the most successful female country singer of the 1990s. Sounding more unashamedly pop than almost any previous released country albums, Shania’s second album, THE WOMAN IN ME, sold more than eight million copies, and sold more quickly than any female country album in music history.

What has helped hook the American record-buying public is the thump of stadium rock and bubblegum catchiness of the choruses, but Shania has yet to go out on the road, and there are many in the business who wonder if she can actually carry a tune!

Many of these new teen acts make in-mall appearances. In the case of Shania Twain, that means attracting up to 20,000 screaming starry-eyed teens. Not all aspiring young divas have made that kind of breakthrough. Louisiana-born Amie Comeaux was 17 when she released her first single, What’s She To You, a couple of years ago. The future looked bright for the petite singer with the full, powerful voice. Amie had been singing on local television and in shopping malls since she was a toddler, and typifies all that is fresh, wholesome, honest and sincere about today’s youth and its music. Yet last year, having almost completed a second album, Polydor/A&M-Nashville closed its doors and poor Amie found herself without a record deal at 19.

The same fate has befallen Canada’s Lisa Brokop. Like Amie, Lisa had been singing around her hometown for years and signed to Capitol-Nashville at just 18 years old. The problem was that she had already matured into a sensitive performer. Though capable of performing bouncy pop tunes, she prefers to perform material that is lyrically deeper. Songs like She Can’t Save Him and Now That We Are Not A Family simply didn’t suit the burgeoning teen market. Consequently Lisa was dropped from the Capitol roster.

However, awaiting in the wings to replace them is a multitude of youngsters like 14-year-old Troy Hedspeth, a regular on Virginia’s Lil’ Ol’ Opry, who has recently completed his second independent label album, and 16-year-old Lila McClain, recently signed to Asylum, with a debut album due in May.

The rise of Teen Country in recent years has seen a drop in album sales, but an increase in single sales, as they hook a young, impressionable audience looking for a quick fix. While it’s easy to view Nashville’s obsession with ever more youthful acts with a degree of cynicism, there is hope. Though many of these new acts are certain to fall by the wayside, a few, with genuine talent, will mature and develop into Vince Gills and Reba McEntires of the 21st century.