Ronnie Milsap – Part Two

After finally deciding to switch from a more rhythm and blues sound to sing country soul, Ronnie and his wife Joyce moved to Nashville. In April, 1973, he signed a recording contract with RCA. His first single for the label, I Hate You, was penned by Dan Penn, his previous record producer in Memphis. A soulful ballad with the country feel provided by unobtrusive steel and tinkling piano, this song gave Ronnie his first country hit, reaching a respectable number ten on the country charts in the summer of that year,

After finally deciding to switch from a more rhythm and blues sound to sing country soul, Ronnie and his wife Joyce moved to Nashville. In April, 1973, he signed a recording contract with RCA. His first single for the label, I Hate You, was penned by Dan Penn, his previous record producer in Memphis. A soulful ballad with the country feel provided by unobtrusive steel and tinkling piano, this song gave Ronnie his first country hit, reaching a respectable number ten on the country charts in the summer of that year,His next release, That Girl Who Waits On Tables, a real tear-jerker with typical country lyrics, also reached the top ten, but Ronnie was hampered a little by his year-long contract with the King of the Road club.

“That stint at the King of the Road did me a lot of good,” he explains, “but by the end of the year I was glad it was behind me. With five nights a week engagement, the only time I was able to get out of Nashville and do promotion or shows in other areas was at the weekend. Throughout that year I became really well-known in Nashville, but I was virtually a nobody in the rest of the country.”

By the end of the year Ronnie’s reputation in Nashville was sky-high. His stints in clubs and bars had been a good character builder, and by now he was an assured, exciting performer who knew just how to build an act and send his audience away happy. He was blending country ballads, rock‘n’roll numbers, soul tunes and r&b ravers into an act that just about knocked the staid country music fraternity for six.

He had enjoyed two hit singles, released a fine country album in WHERE MY HEART IS and had the usually reserved Chet Atkins predict that the sensation of 1974 would be Ronnie Milsap. That was all within a year of moving to Nashville, and I don’t think even Chet appreciated just how right this prophesy was to be!

That first album for RCA turned out to be a treat for country fans. Produced jointly by Tom Collins and Jack Johnson, there was a slight Charley Pride feel apparent on several of the tracks, but Milsap rose above this with a commitment to the lyrics that has been sadly missing on much of Pride’s work during the past decade. Milsap proved that the feel for a country lyric is inbred. It cannot be manufactured, it is built into a singer from birth and has much to do with the area and where you grow up and the hardships suffered on the way.

It appears that people who cannot see seem able to compensate with an uncommon amount of feeling; on this album Ronnie bares his soul on some stunning songs, must notably Where Love Goes When It Dies, Brothers, Strangers And Friends and You’re Stronger Than Me, the latter an old Hank Cochran song first recorded by the late Patsy Cline back in 1962.

When his stint at the King of the Road ended in January, 1974, Ronnie’s career received a further massive boost when he was invited to join the Charley Pride Show.

“The band that I had disintegrated because I had to travel as a single artist,” explains Ronnie. “I started working with Charley in January, and I played with him for about 15 months. I was also having to do other work in night clubs and package shows, because Charley doesn’t work a lot of days, and I need to work a lot.”

“1974 was really my first year getting the taste of what working on the road is all about. I really enjoy it, working with Charley gave me the chance of seeing the world, meeting people and learning and promoting country music. That was the year we felt like we got hold of things and started having number one records. It really was a great beginning. Instead of playing a club of three or four hundred people, I was playing on the stage to six or seven thousand people.”

Ronnie’s string of number one records began in March of that year with Pure Love, an Eddie Rabbitt song full of optimistic lyrics and a fine sing-along melody. He followed that with a new recording of Kristofferson’s Please Don’t Tell Me How The Story Ends, a song that he originally recorded for Warner Brothers in 1971. A slow-moving song performed with delightful delicacy by the excellent Milsap and the Nashville session men, with the sort of sympathetic arrangement that comes only from heaven; this time he had a number one country hit.

The hat-trick of number ones for that year was completed by a stunning revival of Don Gibson’s (I’d Be) A Legend In My Time. Ronnie recalls that he’d listened to Don Gibson on a Knoxville radio station and sung just about every song Gibson ever did except ‘Legend In My Time.’

“Jack Johnson, my manager, suggested I do that song,” Ronnie recalls, “so we changed it around from ¾ to 4/4 and altered the melody around a little bit, by the time we finished with it, the song just about suited me perfectly.”

Ronnie’s second album for RCA, PURE LOVE, showed quite a change from his label debut. There was still a strong country feel, but the strong fiddle and steel work of WHERE MY HEART IS was sweetened by strings and the vocal accompaniment, provided by members of The Joranaires and The Nashville Edition, was much fuller. It was still a good country album, but the smoother edges made it more acceptable for a wider audience.

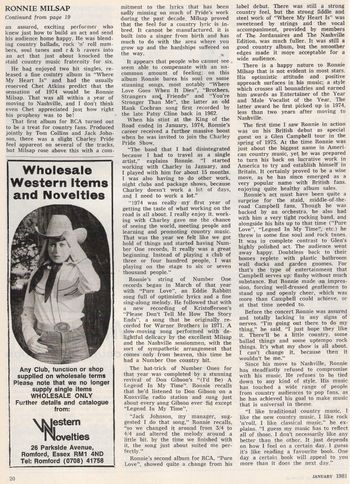

There is a happy nature to Ronnie Milsap that is not evident in most stars. His optimistic attitude and positive approach surfaces in his music; a style which crosses all boundaries and earned him awards as Entertainer of the Year and Male Vocalist of the Year. The latter award first picked up in 1974, less than two years after moving to Nashville.

The first time I saw Ronnie in action was on his British debut as special guest on a Glen Campbell tour in the spring of 1975. At the time Ronnie was just about the biggest name in American country music, yet he was prepared to turn his back on lucrative work in America to try and establish himself in Britain. It certainly proved to be a wise move, as he has since emerged as a very popular name with British fans, enjoying quite healthy album sales.

Ronnie’s act must have been quite a surprise for the staid, middle-of-the-road Campbell fans. Though he was backed by an orchestra, he also had with him a very tight rocking band, and alongside his hits up to that time (Pure Love, Legend In My Time, etc.) he threw in some fine soul and rock tunes. It was in complete contrast to Glen’s highly polished act. The audience went away happy. Doubtless back to their homes replete with plastic bathroom wall ducks and garden gnomes. For that’s the type of entertainment that Campbell serves up; flashy without much substance. But Ronnie made an impression, forcing well-dressed gentlemen to stand up and openly cheer, which was more than Campbell could achieve, or at that time needed to.

Before the concert Ronnie was assured and totally lacking in any signs of nerves. “I’m going out there to do my thing,” he said. “I just hope they like it. There’ll be a little country, some ballad things and some up-tempo rock things. It’s what my show is all about, I can’t change it, because then it wouldn’t be me.”

Since his move to Nashville, Ronnie has steadfastly refused to compromise with his music. He refuses to be tied down to any kind of style. His music has touched a wide range of people from country audiences to pop fans, as he has achieved his goal to make music that is universal in theme.

“I like traditional country music, I like the new country music, I like rock‘n’roll, I like classical music,” he explains. “I guess my music has to reflect all of those. I don’t necessarily like any better than the other. It just depends on how I feel on a certain day. I guess it’s like reading a favourite book. One day a certain book will appeal to you more than it does the next day.”

Throughout 1975 Ronnie maintained his stranglehold on the country charts. Too Late To Worry, Too Blue To Cry, an old Al Dexter song from the 1940s, which he included on his third RCA album, A LEGENED IN MY TIME, made the top five, followed by a happy, optimistic John Schweers’ song, Daydreams About Night Things, which gave Ronnie his fourth number one. That was followed by Hugh Moffatt’s superb ballad Just in Case, which made the top four. Also two of his old Warner Brothers recordings, She Even Woke Me Up To Say Goodbye and A Rose By Any Other Name, made the charts.

A LEGEND IN MY TIME was named Album of the Year in 1975, although to be honest I feel the album won because Ronnie was on a winning streak, and not because it was a classic album. She Came Here For The Change and self-penned Country Cookin’ are among the highlights, but the creative climax comes with Ronnie’s definitive reading of I Honestly Love You. He showed with this album that he possessed the ability to become a major pop star as well as retaining his country audience.

He is always quick to point out, though, that he has never gone out for crossover appeal in his recordings. “I don’t think any artist goes in the studio and says: ‘Hey, guys, we’re gonna cut a crossover record today,’” he says. “It just seems that the trends of country music have moved so far that country music has stretched out. The music is not only accepted in the United States, but is now accepted in Europe, it’s accepted in Australia, it’s accepted in Japan. Therefore I know people are seeking country music.”

Ronnie first half-dozen albums for RCA kept the traditional country music feeling to the forefront. Songs like Borrowed Angel and Who’ll Turn The Lights Out (In Your World Tonight) from the album NIGHT THINGS and Looking Out The Window Through The Pain and You Snap Your Fingers from 20-20 VISION retained that traditional feeling, whilst the hit songs, What Goes On When The Sun Goes Down and (I’m A) Stand By My Woman Man, had a slightly more pronounced pop flavouring.”

“In my mind, the two elements that change country music are the writers of country music songs and the fans of country music,” explains Ronnie. “They pretty much determine where country music is going is going. Things are different to how they were when I first started recording in Nashville. There used to be a lot of steel guitar and fiddle; now, instead of fiddles, you have maybe 20 violins and eight or ten singers. It’s a bigger sound, more urban than it used to be. But to me, as a singer, I feel that I’m still communicating.”

If communicating can be measured in sales of records and concert success, then Ronnie is certainly on the right track. His album, RONNIE MILSAP LIVE, released at the end of 1976, demonstrated to those who had not caught this remarkable performer in concert, just how electrifying he is. In front of an audience seems to be Milsap’s natural habitat, and this album, recorded in Nashville, captured him at his best.

His own road band was augment by top Nashville musicians like Charlie McCoy, Shane Keister, Jimmy Capps and Tommy Williams. He featured several of his hit recordings, plus a version of Kaw-Liga dedicated to Charley Pride, and a stunning reading of Honky Tonk Women, which acted as a fitting climax to a great show.

This album was to act as the closing of one facet of the Ronnie Milsap career and the beginning of a new side, which previously had only been hinted at. A number one single, Let My Love Be Your Pillow, was lifted from the album, and that was followed by the single, It Was Almost Like A Song. A quality pop ballad co-written by Archie Jordan and Hal David, it utilised a full pop production, but still soared to the top spot on the country charts, as did the follow-up, the equally poppy What A Difference You’ve Made In My Life.

Although this audience had broadened, Ronnie continued to avoid musical classification with each new work. In the 1977 CMA Awards he was named Entertainer of the Year, Male Vocalist and also won the Album of the Year award. He is determined to maintain his country following, yet he doesn’t want to let his music to stand still.

“The main key is to be believable,” he says. “I know as a fan myself of certain artists, I listen to them sing, and I want to feel it’s a story or chapter out of their life. I want them to sing and not just read the words. The unique thing about country singers is that they usually sound like they’ve lived it.”

“I still feel like I’m communicating in that fashion,” he continues, “although I’ve been fortunate to have a crossover record. I’m just happy that my music is crossing over. I gotta say that the people who come to my shows are sure they like it. They say: ‘Ronnie, I was never a country music fan, but if you’re singing country music, I love it.’ So with the music, we’re making new fans all over the world. I think that’s good for country music.”

Whether a British country fan would accept an album like IT WAS ALMOST LIKE A SONG, or the follow-up, ONLY ONE LOVE IN MY LIFE, as country, is open to the kind of discussion that has been raging for years. In terms of creativity, polish, feeling, emotion and lyrical expertise, these albums can hardly be faulted. After a series of country-rooted albums, from which he had built a solid following, Ronnie has emerged into one of the strongest crossover artists of the past three years.

One of the special voices in modern music (it is no longer sufficient to constrain him with the ‘country’ tag—he is completely the equal of say Barry Manilow or Burton Cummings as a musical interpreter and communicator of white American ideals), his albums fully demonstrate the new mood of thinking in Nashville with regard to country music and what is accpetable to the country fan.

He has maintained a string of top-selling singles with songs life Only One Love In My Life, Let’s Take The Long Way Around The World, Nobody likes Sad Songs and Why Don’t You Spend The Night. They could hardly be termed standard country fare, being big production, dramatic ballads with full string sections, synthesisers and harmony voices building up a heavy chorus. The effect of these records is quite startling, it seems that at long last Milsap has found the perfect style of expression; a kind of unique blend of his classical music upbringing, his natural country roots and a strong feeling for contemporary music.

He has taken his music uptown, but without losing feeling, exuberance or sight of what he had in mind. He has followed the same route as Charlie Rich, Glen Campbell and Ray Price but, unlike that trio, Ronnie has always maintained a strong control over his music. He is interested in experimenting with new sounds in the studio and has a great fascination for synthesisers, feeling that if used wisely they can enhance the music.

A couple of years ago he realised another of his great ambitions when the building of his own recording studio, Ground Star Laboratory, was completed in Nashville. He is almost more enthusiastic about the studio than he is about his music.

“A few people who have worked with me in the studio all got together and we designed our own place to work,” he explains. “We built a building in Nashville. It’s the most technical and electronically by far ahead of anything else in country. It’s comparable to a few things I’ve seen in Hollywood—a few I’ve seen in London.”

The first record to emerge from the new studio was the IMAGES album, one of the artist’s most eloquent records. Included is one of my favourite Milsap performances, Nobody Likes Sad Songs, a superb Bob McDill/Wayland Holyfield song that deservedly made the top spot in the country charts in the spring of 1979. This is one of those albums where almost any track could have been lifted as a successful and commercial single.

The overly romantic tunes include All Good Things Don’t Have To End, an optimistic outlook at finding a love; Archie Jordan and Richard Leigh’s subtle In No Time At All; the teary-eyed You Don’t Look For Love and the old country standard I Really Don’t Want To Know. The album’s great surprise is Milsap’s rendition of Get It Up, a high–energy, kick-it-out rocker that is a long way from his customary middle-of-the-road ballads.

The blatantly funky-disco-rock strains of Get It Up certainly raised more than a few eyebrows in country music circles on both sides of the Atlantic. The song was released as the ‘B’ side of In No Time At All, a ballad that rose high on the country charts. Soon RCA discovered that Get It Up was gaining plays in discos and getting exposure on the rock radio stations. They wasted no time in pressing special 12-inch disco copies, and eventually it became Ronnie’s most successful record on the American pop charts.

Sensibly, Ronnie made no attempt to follow his fluke success with anything remotely similar. Instead he released Bob McDill’s Why Don’t You Spend The Night, a highly commercial, big ballad affair that naturally made it all the way to the top of the country charts. Again it was recorded in Milsap’s own Ground Star Studio, the 40-track facility on Music Row. A dream come true for the singer, the studio allows him to be as well-versed in the technical aspects of his own recordings as he is in the creative end.

He has already begun using his studio projects, having produced recordings by Darrell McCall, a man who has been around the country scene for more than 20 years, but never realised his potential. Perhaps, now with Milsap guiding him, that long awaited success will come McCall’s way.

Milsap himself has undergone management changes during the past year in an effort to broaden his horizons even wider. He has changed management being handled now by Dan Cleary of the Los Angeles-based BNB Management. Milsap hopes that the change will bring him and his music even wider recognition—he even has ambitions to appear on TV, not just as a performer but also handling dramatic roles.

“I’m the age now where I feel I can branch out and explore new directions without losing my country audiences,” Ronnie said when he was in Britain for his Wembley appearance in 1979. “I’m experimenting with synthesisers and other electronic instruments on my recordings, yet I’m still retaining that country feel that is there in the songs. I just cannot stand still, I get a little impulsive at times and maybe a little impatient because I want things to happen immediately—but it all takes time.”

In the eight years that Ronnie has been in Nashville, things have certainly happened for him in a big way, and there doesn’t seem to be any slowing down in his run of hit singles, which are still the very lifeblood of a successful country music career. During the past year he has scored on the charts with Why Don’t You Spend The Night, Cowboys And Clowns, Silent Night (After The Fight) and Smokey Mountain Rain.

His album, MILSAP MAGIC, is another superb example of what can be achieved by sensibly blending country and easy-listening styles into a compelling and rich musical blend. It ranks as his most uplifting, self-assuring work that displays Ronnie coming to terms with himself and his craft. The album’s delight is his moody reworking of She Thinks I Still Care, and that’s followed by a fine up-tempo beauty, My Heart, which is full of the optimism that embodies the character of Milsap himself.

It is this optimistic approach to what he is doing that has enabled Ronnie Milsap to reach out and achieve so much in the music business. He has brushed aside the handicap of being blind, ignored those who said he couldn’t do it, and made his way to the very top by doing what he has always wanted to—making people happy with his music.

First published in Country Music People, January 1981