Johnny Rodriguez ('79)

First published in Country Music People, August 1979

A quick rise to the top is something more commonly associated with the rock field than with country music, but after less than two years in the music business, Johnny Rodriguez had notched up half-a-dozen top 10 singles and three best selling albums.

A quick rise to the top is something more commonly associated with the rock field than with country music, but after less than two years in the music business, Johnny Rodriguez had notched up half-a-dozen top 10 singles and three best selling albums.

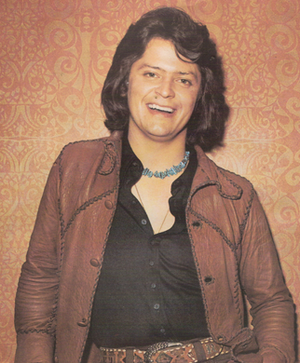

He gained attention in 1973 as the first Mexican-American country star, as well as being one of the youngest (20 at the time), artists to make it in country. His string of hits and successful appearances since then, however, indicate that he is no mere flash in the pan. Though it would be true to say that the initial promise shown in his recordings, has at times, sadly deserted him.

The black-haired, green-eyed singer-songwriter, who stands 5 feet 6 inches, is a gifted singer. The owner of a deep, emotionally honest voice, properly raunchy on honky-tonk numbers and mellow and light on mood numbers. At the outset of his career his trademark was to break into a sexy verse of Spanish when you least expected it, and to end slow songs with a quivering vibrato that wreaks of pleading, unsatisfied pain.

His rise to the top is a textbook American dream story all the way. He grew up in Sabinal, Texas, a town with a population of 1,800 people about 90 miles from the Mexican border. He is the second youngest of a family of eight, but was the only member to show a lasting interest in music.

“I grew up in a small country town and my family was poor,” he reflects. “I know what struggling is. But I was always around music while I was growing up, and I decided to sing country because that’s what I am. My older brother, who has passed away, was a rodeo rider and he’d sing a lot of country songs in Spanish. That’s where I came up with the idea of doing some of my songs half in English and half in Spanish.”

A few years back, after a night out on the beer, he and some friends rustled three goats (allegedly they were looking for deer, but goat is a staple diet among the Texas’ Mexican population), for a barbecue. Thrown in jail, awaiting sentencing, he played guitar and impressed Texas Ranger Joaquin Jackson to the extent that he introduced him to ‘Happy’ Shahan, owner of a tourist attraction called Alamo Village, the site of the movie The Alamo. There, Johnny became a singer-stagecoach driver, chancing to meet Nashville star Tom T. Hall, who lured him to Music City.

With his father having recently died of cancer and his rodeo-riding brother being killed in a car crash, Johnny didn’t have much to lose, he set out, arriving in Nashville with eight dollars in his pocket and called Hall, who offered him the lead guitar spot in his road band, The Storytellers, and introduced him to Mercury Records a&r man, Roy Dea. Halfway through his first try-out song, the Don Gibson classic I Can’t Stop Loving You, Johnny broke into a Spanish verse, Dea was so overcome he offered him a recording contract on the spot.

This was the autumn of 1972 and Johnny’s initial release, and first hit was Pass Me By, followed by an excellent debut album, INTRODUCING JOHNNY RODRIGUEZ. Four of the songs were co-written with Tom T. Hall, and two he did himself. It was mostly laid-back country, dealing with loneliness, wandering and being your own man. The instrumentation is bare and basic, highlighted by some great fiddle-steel guitar complements. There was no vocal accompaniment, just the earthy, real goods.

Producer Jerry Kennedy stuck with this general format for the next effort, ALL I EVER MEANT TO DO WAS SING. The intimate atmosphere still prevailed, as did Rodriguez’s sadness. Five of the songs were his, describing lost love, taking off (as in the hit Riding My Thumb To Mexico) and seeing a friend die of alcohol in an up-tempo classic Jimmy Was A Drinkin’ Kind Of Man.

Johnny stated shortly after the release of this second album his desire to stay close to country music. “It would be nice to have a crossover hit,” he said, “but I’m not going out to try for one. If it happens, great, but if it doesn’t that’s okay, too. I think one of the biggest mistakes you can make is to try from the outset for country and pop at the same time. I grew up with country music, and that’s the music I want to stay with.”

But the wind did start to change direction. With MY THIRD ALBUM and SONGS ABOUT LADIES AND LOVE, there came more of a pop sound. Orchestrated strings, trumpet, vibes and vocal accompaniment are increasingly heard trying to force the fiddle, steel guitar and Dobro out. When making his British debut at Wembley in 1974 Johnny admitted: “Country fans are going to think I’ve changed my style. Some will say I’m not doing country. I think that’s wrong. I know I’m country so I’ll do a song like Something because it really is a good song. I’ll do a cut like Ramblin’ Man for the same reason. It may be rock, but that’s a song Hank Williams could have written.”

A waltzy feel occasionally came in and he even did pop versions of We’re Over and Turn Around Look At Me. In a few instances the edge was dropped from his voice and he sounded quite a bit like Charlie Rich. He still did the music well, but to me it was just not his best style.

With the release of his fifth album, JUST GET UP AND CLOSE THE DOOR, he returned to the early country style, to the solid, understated power that had dominated his first two albums. The title tune, a number one country hit, written by Linda Hargrove, was given a beautiful pop-country reading by the young singer. His only other concession to the commercial sounds came with the rock tune, C.C. Rider, which to be fair, he handled with real assurance.

In between these two songs he seemed to have forsaken the pop directions and opted for straight and progressive country. You’ll find impressive versions of two songs by Billy Joe Shaver, a ballad by Willie Nelson called The Sound In Your Mind, and a handful of country standards. Only one of the songs was self-written, but it did appear that he had settled into an established style.

When it comes to singing a country song, hardly anyone does it better than Rodriguez. “I’ve always liked country music,” he says, “and everywhere I go, whether it’s an audience of 16-20 years old or 25-45, they always like country music and I like singing it.”

If that’s the case, then why does he allow himself to record pop songs like My Way (a superb song for a singer twice his age), Torn Between Two Lovers, Spanish Eyes, Bridge Over Troubled Water and Love Me With All Your Heart. And perhaps more importantly, why are the Nashville Philharmonic allowed to spread their sickly string sections all over his recordings?

“As a whole, I think all kinds of music, even country music has to go through a change,” he explains. “I try to change my own music with each album—expand it a little—so it never stays the same.”

Rodriguez certainly made an unprecedented impact on Nashville six years ago, but the problems of making such an explosive entry is that everything after tends to be something of an anti-climax. Recently there has definitely been a deterioration in his recordings, although he has continued to increase his popularity and the musicianship on his albums is always excellent.

The problem is that everyone now expects him to serve up something new and exciting, and really, it’s just not been happening. He has had an erratic career, his work always consistent in terms of achievement, with each release containing real flashes of inspiration and moments of pure musical genius.

Bob McDill’s It Took Us All Night To Say Goodbye, with Pete Drake’s distinctive steel guitar, Bobby Bond’s There’ll Always Be Honky Tonks In Texas with Johnny Gimble’s stylised fiddle, and his own, Tell All Your Troubles To Me, are just three examples that spring to mind. He shows himself to be one of the finest singers I’ve heard, with a style that’s deceptively calm, but at the same time striking and commanding.

Yet there is always the other side of the coin, and I never thought I would see the day when I would have to describe a Johnny Rodriguez record as ordinary. LOVE ME WITH ALL YOUR HEART, both the album and the single are overloaded with plush strings. Also this is the only one of his albums not to contain any self-written material. As a songwriter, this young man has a lot going for him. No way does he need to turn to hackneyed songs like Ramblin’ Rose or Spanish Eyes to pad out his albums.

Nowadays it seems that Rodriguez’s heart and soul has been eroded whilst striving for perfection. Concentrating more intensely on arrangements and greater technical proficiency, his music has lost much of the exuberance and feeling that characterised his early work. This album lends a fair bit of ammunition to that argument for it is his most arranged and contrived work. He does touch the heights (Rest Your Love On Me, stands as one of the best things he’s ever done), and the album as a whole has many strengths, but there’s a certain bland, remote atmosphere about it all.

But the singer is still emphatic about his country music: “I still try and reach country audiences most of the time,” he explains. “And I also want to keep trying to reach the Latin audiences. If my name had not been Rodriguez, I might not have moved up nearly so fast.”

“For me,” he continues, “the Latin audiences in Texas have often made the difference between playing for a half-filled house and a sell-out. And in other areas of the Southwest, these audiences between a poor turn out and a full house.”

You’ll find the odd song on his albums put there to tempt the several million Chicanos who live in the Southwest. Don’t be frightened off a Johnny Rodriguez album because of a foreign song title. Quite often you’ll be in for a pleasant surprise, because the songs that are tailored for his Latin fans are sometimes the pick of an album. The self-penned Que To Quero from the superb JUST FOR YOU album is a good example. With effective Mexican trumpets blended with the steel guitar of Weldon Myrick, this turns out to be a good Tex-Mex country love ballad. In a more traditional vein is Ers Tu, which receives a smooth reading and is quite cute.

Throughout his six year stay with Mercury, which has taken him through a surprising twelve albums, Johnny has been well-served by producer Jerry Kennedy. Kennedy’s one fault, and it also shows through on recordings by Faron Young, Tom T. Hall and Jerry Lee Lewis, is his lack of adventure. In fact, as a producer he often fails to bring out the best in the artists he is working with. At times on his albums, Rodriguez seems to be just singing along, then on another song he really gets to grips and puts his heart and soul into what he is doing. It is the producer who should keep a singer like Rodriguez on his toes all the time.

At the end of last year, the young Texan signed a new contract with Epic, this time coming under the guidance of Billy Sherrill, a brilliant producer, but on paper, not the right choice for Rodriguez. He is unlikely to guide Johnny back to the basic country sounds that first established him as a major star. The Rodriguez move into Glen Campbell pop-country can now only be speeded up. A great pity this, but then again Sherrill does have the knack to bring the best, vocally, out of the artists he works with. He has proved that with Tammy Wynette, David Houston and George Jones.

Perhaps my fears of Rodriguez coming under the control of Billy Sherrill will prove to be unfounded. Certainly the new partnership must improve upon the last two albums released by Mercury. They both fell short of the promise of JUST FOR YOU, seeming as if the toll of something like a dozen albums and many years on the road and continuous pressure had dented Rodriguez’s incentive and energy.

He has many years in front of him in country music. Even now, seven years after his amazing debut, he is still one of the youngest stars around, and I do feel that his heart is in the right place, even if I don’t always agree with the material he chooses to record, the way it is produced, and the feeling he imparts.

The final words from this young man are refreshingly honest and very wise: “All I want from the fans is that they believe what I sing. If they believe what I sing and what I write, that means more to me than anything.”

A quick rise to the top is something more commonly associated with the rock field than with country music, but after less than two years in the music business, Johnny Rodriguez had notched up half-a-dozen top 10 singles and three best selling albums.

A quick rise to the top is something more commonly associated with the rock field than with country music, but after less than two years in the music business, Johnny Rodriguez had notched up half-a-dozen top 10 singles and three best selling albums.He gained attention in 1973 as the first Mexican-American country star, as well as being one of the youngest (20 at the time), artists to make it in country. His string of hits and successful appearances since then, however, indicate that he is no mere flash in the pan. Though it would be true to say that the initial promise shown in his recordings, has at times, sadly deserted him.

The black-haired, green-eyed singer-songwriter, who stands 5 feet 6 inches, is a gifted singer. The owner of a deep, emotionally honest voice, properly raunchy on honky-tonk numbers and mellow and light on mood numbers. At the outset of his career his trademark was to break into a sexy verse of Spanish when you least expected it, and to end slow songs with a quivering vibrato that wreaks of pleading, unsatisfied pain.

His rise to the top is a textbook American dream story all the way. He grew up in Sabinal, Texas, a town with a population of 1,800 people about 90 miles from the Mexican border. He is the second youngest of a family of eight, but was the only member to show a lasting interest in music.

“I grew up in a small country town and my family was poor,” he reflects. “I know what struggling is. But I was always around music while I was growing up, and I decided to sing country because that’s what I am. My older brother, who has passed away, was a rodeo rider and he’d sing a lot of country songs in Spanish. That’s where I came up with the idea of doing some of my songs half in English and half in Spanish.”

A few years back, after a night out on the beer, he and some friends rustled three goats (allegedly they were looking for deer, but goat is a staple diet among the Texas’ Mexican population), for a barbecue. Thrown in jail, awaiting sentencing, he played guitar and impressed Texas Ranger Joaquin Jackson to the extent that he introduced him to ‘Happy’ Shahan, owner of a tourist attraction called Alamo Village, the site of the movie The Alamo. There, Johnny became a singer-stagecoach driver, chancing to meet Nashville star Tom T. Hall, who lured him to Music City.

With his father having recently died of cancer and his rodeo-riding brother being killed in a car crash, Johnny didn’t have much to lose, he set out, arriving in Nashville with eight dollars in his pocket and called Hall, who offered him the lead guitar spot in his road band, The Storytellers, and introduced him to Mercury Records a&r man, Roy Dea. Halfway through his first try-out song, the Don Gibson classic I Can’t Stop Loving You, Johnny broke into a Spanish verse, Dea was so overcome he offered him a recording contract on the spot.

This was the autumn of 1972 and Johnny’s initial release, and first hit was Pass Me By, followed by an excellent debut album, INTRODUCING JOHNNY RODRIGUEZ. Four of the songs were co-written with Tom T. Hall, and two he did himself. It was mostly laid-back country, dealing with loneliness, wandering and being your own man. The instrumentation is bare and basic, highlighted by some great fiddle-steel guitar complements. There was no vocal accompaniment, just the earthy, real goods.

Producer Jerry Kennedy stuck with this general format for the next effort, ALL I EVER MEANT TO DO WAS SING. The intimate atmosphere still prevailed, as did Rodriguez’s sadness. Five of the songs were his, describing lost love, taking off (as in the hit Riding My Thumb To Mexico) and seeing a friend die of alcohol in an up-tempo classic Jimmy Was A Drinkin’ Kind Of Man.

Johnny stated shortly after the release of this second album his desire to stay close to country music. “It would be nice to have a crossover hit,” he said, “but I’m not going out to try for one. If it happens, great, but if it doesn’t that’s okay, too. I think one of the biggest mistakes you can make is to try from the outset for country and pop at the same time. I grew up with country music, and that’s the music I want to stay with.”

But the wind did start to change direction. With MY THIRD ALBUM and SONGS ABOUT LADIES AND LOVE, there came more of a pop sound. Orchestrated strings, trumpet, vibes and vocal accompaniment are increasingly heard trying to force the fiddle, steel guitar and Dobro out. When making his British debut at Wembley in 1974 Johnny admitted: “Country fans are going to think I’ve changed my style. Some will say I’m not doing country. I think that’s wrong. I know I’m country so I’ll do a song like Something because it really is a good song. I’ll do a cut like Ramblin’ Man for the same reason. It may be rock, but that’s a song Hank Williams could have written.”

A waltzy feel occasionally came in and he even did pop versions of We’re Over and Turn Around Look At Me. In a few instances the edge was dropped from his voice and he sounded quite a bit like Charlie Rich. He still did the music well, but to me it was just not his best style.

With the release of his fifth album, JUST GET UP AND CLOSE THE DOOR, he returned to the early country style, to the solid, understated power that had dominated his first two albums. The title tune, a number one country hit, written by Linda Hargrove, was given a beautiful pop-country reading by the young singer. His only other concession to the commercial sounds came with the rock tune, C.C. Rider, which to be fair, he handled with real assurance.

In between these two songs he seemed to have forsaken the pop directions and opted for straight and progressive country. You’ll find impressive versions of two songs by Billy Joe Shaver, a ballad by Willie Nelson called The Sound In Your Mind, and a handful of country standards. Only one of the songs was self-written, but it did appear that he had settled into an established style.

When it comes to singing a country song, hardly anyone does it better than Rodriguez. “I’ve always liked country music,” he says, “and everywhere I go, whether it’s an audience of 16-20 years old or 25-45, they always like country music and I like singing it.”

If that’s the case, then why does he allow himself to record pop songs like My Way (a superb song for a singer twice his age), Torn Between Two Lovers, Spanish Eyes, Bridge Over Troubled Water and Love Me With All Your Heart. And perhaps more importantly, why are the Nashville Philharmonic allowed to spread their sickly string sections all over his recordings?

“As a whole, I think all kinds of music, even country music has to go through a change,” he explains. “I try to change my own music with each album—expand it a little—so it never stays the same.”

Rodriguez certainly made an unprecedented impact on Nashville six years ago, but the problems of making such an explosive entry is that everything after tends to be something of an anti-climax. Recently there has definitely been a deterioration in his recordings, although he has continued to increase his popularity and the musicianship on his albums is always excellent.

The problem is that everyone now expects him to serve up something new and exciting, and really, it’s just not been happening. He has had an erratic career, his work always consistent in terms of achievement, with each release containing real flashes of inspiration and moments of pure musical genius.

Bob McDill’s It Took Us All Night To Say Goodbye, with Pete Drake’s distinctive steel guitar, Bobby Bond’s There’ll Always Be Honky Tonks In Texas with Johnny Gimble’s stylised fiddle, and his own, Tell All Your Troubles To Me, are just three examples that spring to mind. He shows himself to be one of the finest singers I’ve heard, with a style that’s deceptively calm, but at the same time striking and commanding.

Yet there is always the other side of the coin, and I never thought I would see the day when I would have to describe a Johnny Rodriguez record as ordinary. LOVE ME WITH ALL YOUR HEART, both the album and the single are overloaded with plush strings. Also this is the only one of his albums not to contain any self-written material. As a songwriter, this young man has a lot going for him. No way does he need to turn to hackneyed songs like Ramblin’ Rose or Spanish Eyes to pad out his albums.

Nowadays it seems that Rodriguez’s heart and soul has been eroded whilst striving for perfection. Concentrating more intensely on arrangements and greater technical proficiency, his music has lost much of the exuberance and feeling that characterised his early work. This album lends a fair bit of ammunition to that argument for it is his most arranged and contrived work. He does touch the heights (Rest Your Love On Me, stands as one of the best things he’s ever done), and the album as a whole has many strengths, but there’s a certain bland, remote atmosphere about it all.

But the singer is still emphatic about his country music: “I still try and reach country audiences most of the time,” he explains. “And I also want to keep trying to reach the Latin audiences. If my name had not been Rodriguez, I might not have moved up nearly so fast.”

“For me,” he continues, “the Latin audiences in Texas have often made the difference between playing for a half-filled house and a sell-out. And in other areas of the Southwest, these audiences between a poor turn out and a full house.”

You’ll find the odd song on his albums put there to tempt the several million Chicanos who live in the Southwest. Don’t be frightened off a Johnny Rodriguez album because of a foreign song title. Quite often you’ll be in for a pleasant surprise, because the songs that are tailored for his Latin fans are sometimes the pick of an album. The self-penned Que To Quero from the superb JUST FOR YOU album is a good example. With effective Mexican trumpets blended with the steel guitar of Weldon Myrick, this turns out to be a good Tex-Mex country love ballad. In a more traditional vein is Ers Tu, which receives a smooth reading and is quite cute.

Throughout his six year stay with Mercury, which has taken him through a surprising twelve albums, Johnny has been well-served by producer Jerry Kennedy. Kennedy’s one fault, and it also shows through on recordings by Faron Young, Tom T. Hall and Jerry Lee Lewis, is his lack of adventure. In fact, as a producer he often fails to bring out the best in the artists he is working with. At times on his albums, Rodriguez seems to be just singing along, then on another song he really gets to grips and puts his heart and soul into what he is doing. It is the producer who should keep a singer like Rodriguez on his toes all the time.

At the end of last year, the young Texan signed a new contract with Epic, this time coming under the guidance of Billy Sherrill, a brilliant producer, but on paper, not the right choice for Rodriguez. He is unlikely to guide Johnny back to the basic country sounds that first established him as a major star. The Rodriguez move into Glen Campbell pop-country can now only be speeded up. A great pity this, but then again Sherrill does have the knack to bring the best, vocally, out of the artists he works with. He has proved that with Tammy Wynette, David Houston and George Jones.

Perhaps my fears of Rodriguez coming under the control of Billy Sherrill will prove to be unfounded. Certainly the new partnership must improve upon the last two albums released by Mercury. They both fell short of the promise of JUST FOR YOU, seeming as if the toll of something like a dozen albums and many years on the road and continuous pressure had dented Rodriguez’s incentive and energy.

He has many years in front of him in country music. Even now, seven years after his amazing debut, he is still one of the youngest stars around, and I do feel that his heart is in the right place, even if I don’t always agree with the material he chooses to record, the way it is produced, and the feeling he imparts.

The final words from this young man are refreshingly honest and very wise: “All I want from the fans is that they believe what I sing. If they believe what I sing and what I write, that means more to me than anything.”