John Fogerty - Blue Moon On The Rise

First Published in Country Music International, August 1997

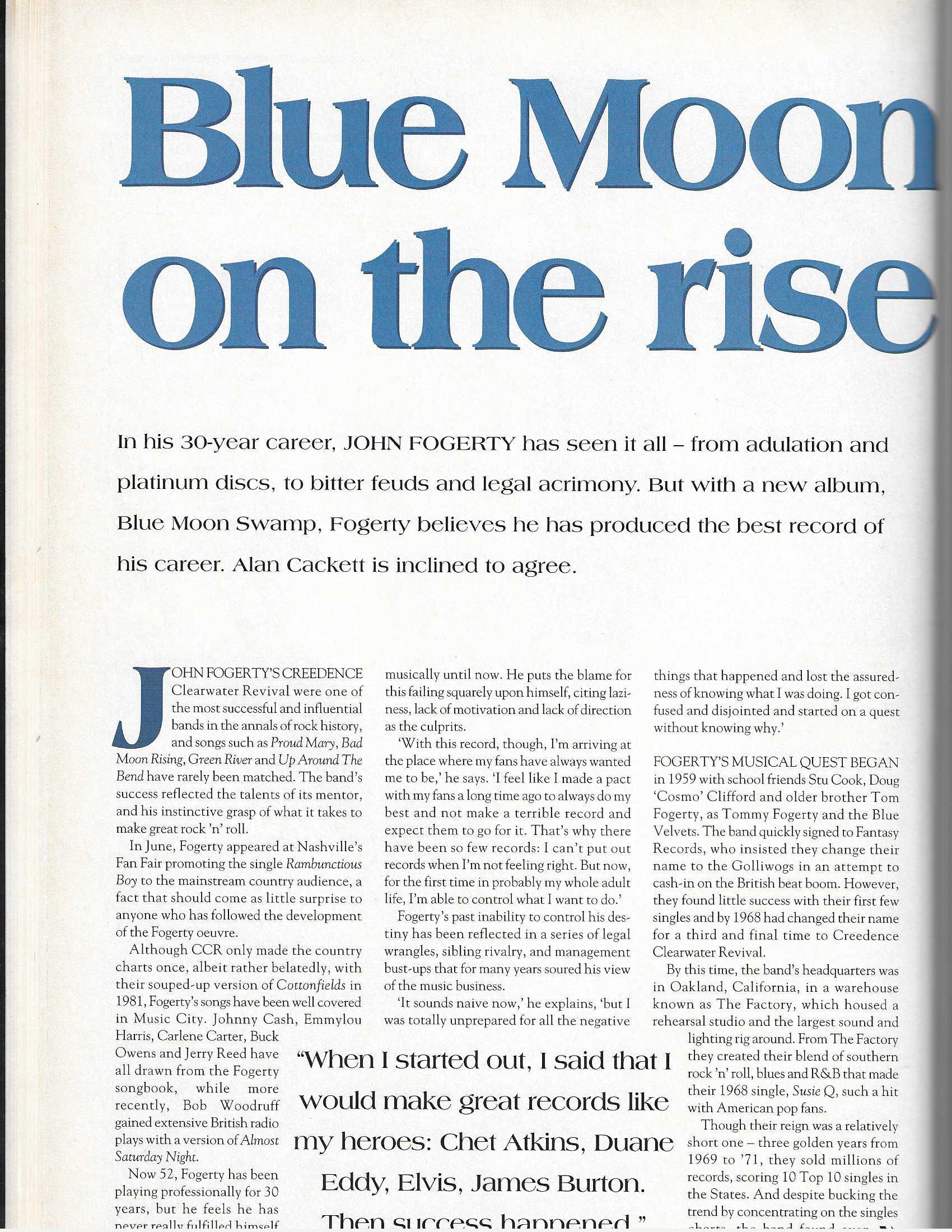

In his 30-year career, John Fogerty has seen it all—from adulation and platinum discs, to bitter feuds and legal acrimony. But with a new album, BLUE MOON SWAMP, Fogerty believes he has produced the best record of his career. Alan Cackett is inclined to agree.

In his 30-year career, John Fogerty has seen it all—from adulation and platinum discs, to bitter feuds and legal acrimony. But with a new album, BLUE MOON SWAMP, Fogerty believes he has produced the best record of his career. Alan Cackett is inclined to agree.

John Fogerty’s Creedence Clearwater Revival were one of the most successful and influential bands in the annuals of rock history, and songs such as Proud Mary, Bad Moon Rising, Green River and Up Around The Bend have rarely been matched. The band’s success reflected the talents of its mentor, and his instinctive grasp of what it takes to make great rock’n’roll.

In June, Fogerty appeared at Nashville’s Fan Fair promoting the single Rambunctious Boy to the mainstream country audience, a fact that should come as a little surprise to anyone who has followed the development of the Fogerty oeuvre.

Although CCR only made the country charts once, albeit rather belatedly, with their souped-up version of Cottonfields in 1981, Fogerty’s songs have been well covered in Music City, Johnny Cash, Emmylou Harris, Carlene Carter, Buck Owens and Jerry Reed have all drawn from the Fogerty songbook, while more recently, Bob Woodruff gained extensive British radio plays with a version of Almost Saturday Night.

Now 52, Fogerty has been playing professionally for 30 years, but he feels he has never really fulfilled himself musically until now. He puts the blame for this failing squarely upon himself, citing laziness, lack of motivation and lack of direction as the culprits.

“With this record, though, I'm arriving at the place where my fans have always wanted me to be,” he says. “I feel like I made a pact with my fans a long time ago to always do my best and not make a terrible record and expect them to go for it. That’s why there have been so few records: I can’t put out the records when I'm not feeling right. But now, for the first time in probably my whole adult life, I'm able to control what I do.”

Fogerty's past inability to control his destiny has been reflected in a series of legal wrangles, sibling rivalry, and management bust-ups that for many years soured his view of the music business.

“It sounds naïve now,” he explains, “but I was totally unprepared for all the negative things that have happened and lost the assuredness of knowing what I was doing. I got confused and disjointed and started on a quest without knowing why.”

Fogerty's musical quest began in 1959 with school friends Stu Cook, Doug ‘Cosmo’ Clifford and older brother Tom Fogerty, as Tommy Fogerty and the Blue Velvets. The band quickly signed to Fantasy Records, who insisted they change their name to the Golliwogs in an attempt to cash-in on the British beat boom. However, they found little success with their first few singles and by 1968 had changed their name for the third and final time to Creedence Clearwater Revival.

By this time, the band’s headquarters was in Oakland, California, in a warehouse known at the Factory, which housed a rehearsal studio and the largest sound and lighting rig around. From the Factory they created their blend of southern rock’n’roll, blues and r&b that made their 1968 single, Suzie Q, such a hit with American pop fans.

Though their reign was a relatively short one—three golden years from 1969 to 1971, they sold millions of records, scoring ten Top 10 singles in the States. And despite bucking the trend by concentrating on the singles charts, the band found even more success with their albums, CREEDENCE CLEARWATER REVIVAL, BAYOU COUNTRY, GREEN RIVER, WILLY & THE POOR BOYS, COSMO’S FACTORY and PENDULUM, all passed the million sales mark within months of their respective release dates.

Throughout this period, Fogerty remained the dominant force in the band—singer, guitarist and songwriter, as well as producer, manager and agent. At the time, he said: “I don’t trust anyone else to handle Creedence’s affairs. Through experience I found I was always the manager, because they had to come to me for all the decisions.” But success for CCR lay in Fogerty’s ability to write such infectious songs as the hillbilly two-step of Bad Moon Rising, or Lodi, which became a big country hit for Buddy Alan.

In album terms, the band reached their peak with 1970’s COSMO’S FACTORY. The album bore the hallmark of great American rock’n’roll with its extended 10-minute version of I Heard It Through The Grapevine and studied revivals of Elvis Presley’s My Baby Left Me and Roy Orbison’s Ooby Dooby.

Grapevine and studied revivals of Elvis Presley’s My Baby Left Me and Roy Orbison’s Ooby Dooby.

However, Fogerty’s dominating presence was also a contributory factor in the band’s collapse. Rivalry with his brother led Tom to quit, and in an unprecedented move, Fogerty allowed his remaining colleagues to share their creative input on the album MADRI GRAS which, in the event resulted in unmitigated disaster.

With CCR no more, Fogerty set about recording his own solo debut, albeit under the banner of mythical band The Blue Ridge Rangers. Fogerty played every note on the record, but his name did not appear on the sleeve, successfully creating the illusion that the group was for real. However, his awesome musical presence ensured that the album found success, with its jumping version of Jambalaya, becoming an American pop hit, as did Hearts Of Stone, while Fogerty turned in a pretty straight country reading of Please Help Me I’m Falling.

Fuelled by the musical freedom the one-man-band approach offered, he was ready to embark upon a solo career, but a dispute with Fantasy led to a three-year recording hiatus before he was able to sign with Asylum. JOHN FOGERTY, his first album for his new label, included the hits Rockin’ All Over The World and Almost Saturday Night. He also recorded a second album, HOODOO, but was so unhappy with the result that he scrapped it before release, destroying all tapes to ensure that no bootlegs were made.

It took nine years to complete the next album, CENTERFIELD, which appeared on Warner Brothers in 1985. The album had an incredible impact, exhibiting as always the sureness of touch associated with Fogerty’s production. The album included Big Train From Memphis, a touching tribute to one of his idols, Elvis Presley, and Vanz Kant Dance, a-not-too-heavily disguised dig at the Fantasy Record’s boss Saul Zaentz.

Less than two years later, Fogerty returned with Eye Of The Zombie, a lacklustre affair that received short shrift from critics and fans alike. In an effort to stay hip and appeal to a broader audience, Fogerty had lost touch with himself.

While working on Eye Of The Zombie Fogerty suffered an accusation of plagiarism brought by Zaentz, claiming that Fogerty had stolen his own chord progression from the Creedence Clearwater Revival hit Run Through The Jungle and inserted it into his song, The Old Man Down The Road from CENTERFIELD. Fogerty was vindicated, but it left the singer more bitter than ever. “It was such a perversion of the spirit of what music should be about,” he says.

One of life’s observers, resolving his thoughts into music, Fogerty has always believed that music is the quickest and most effective media of mass communication. As much as he is a creator of music, he is also a dedicated music fan. A great lover of the blues, he set out to discover the rural roots of the blues, which he knew little about beyond the urban blues giants.

One of life’s observers, resolving his thoughts into music, Fogerty has always believed that music is the quickest and most effective media of mass communication. As much as he is a creator of music, he is also a dedicated music fan. A great lover of the blues, he set out to discover the rural roots of the blues, which he knew little about beyond the urban blues giants.

Some six years ago he took a long, lazy tour through the blues-rich Mississippi Delta. Driving alone he absorbed the elements that have made southern blues and country music so special. Shortly after his return home to California, he began the recording for Blue Moon Swamp, but the music he started working with proved unable to produce the raw rock’n’roll feel that has always been at heart of Fogerty’s work,

“The arrangements just weren’t kicking me in the rear-end like I knew they should,” he explains. “But the problem was only partly the other musicians. The other part was me and the promise I'd made and not lived up to. When I started out playing music I said that I would grow up to be a really good musician and make records like my heroes: Chet Atkins, Duane Eddy, Elvis, James Burton. Then success happened with Creedence Clearwater Revival, and a lot of things went wrong. I got lazy and didn’t progress.”

The fire and enthusiasm that he was looking for came not so much from fellow musicians, but from the Dobro, which he says is the key to everything on his new album. “The Dobro kicked open the door to my becoming the guy I promised I would be.”

One of the songs that came out of his southern journey was A Hundred And Ten In The Shade, a kind of southern-negro field holler. When he first started laying down the demo for the song, he thought that a bottleneck guitar would be the perfect foil for the song, but despite practising for months, it just didn’t come together the way he had envisaged.

Then it came to him, the only way he could get the sound he wanted was with a Dobro. After several more months spent practicing, he finally mastered the Dobro and discovered that the instrument took him to another level, a personal vehicle to another universe and musical experience. Later he found the right, sensitive back-up players for his dream. While he himself played guitar, Irish bouzouki, farfisa organ, tambourine, lap steel, electric sitar, mandolin, and most importantly, Dobro.

The album is heavily influenced by the Southern delta, with lots of the blues and swamp-drenched roots rock style long identified with Fogerty. Delighted with the way the album finally turned out, for the first time in more than 25 years Fogerty will be touring heavily. Also for the first time in as many years, he will be performing several of the old Creedence hits.

“I’m really looking forward to touring and showing people with this record where I am in my life and career,” he says. “All the way back to my Creedence days I’d pictured a life of touring, interrupted by recording albums, but so many things came along and affected my life other than what I thought I was going to do. Now I have the opportunity to get back to what I love the most, the music.”