Jim Lauderdale - A Prophet Without Honour

First Published in Country Music International – July 1998

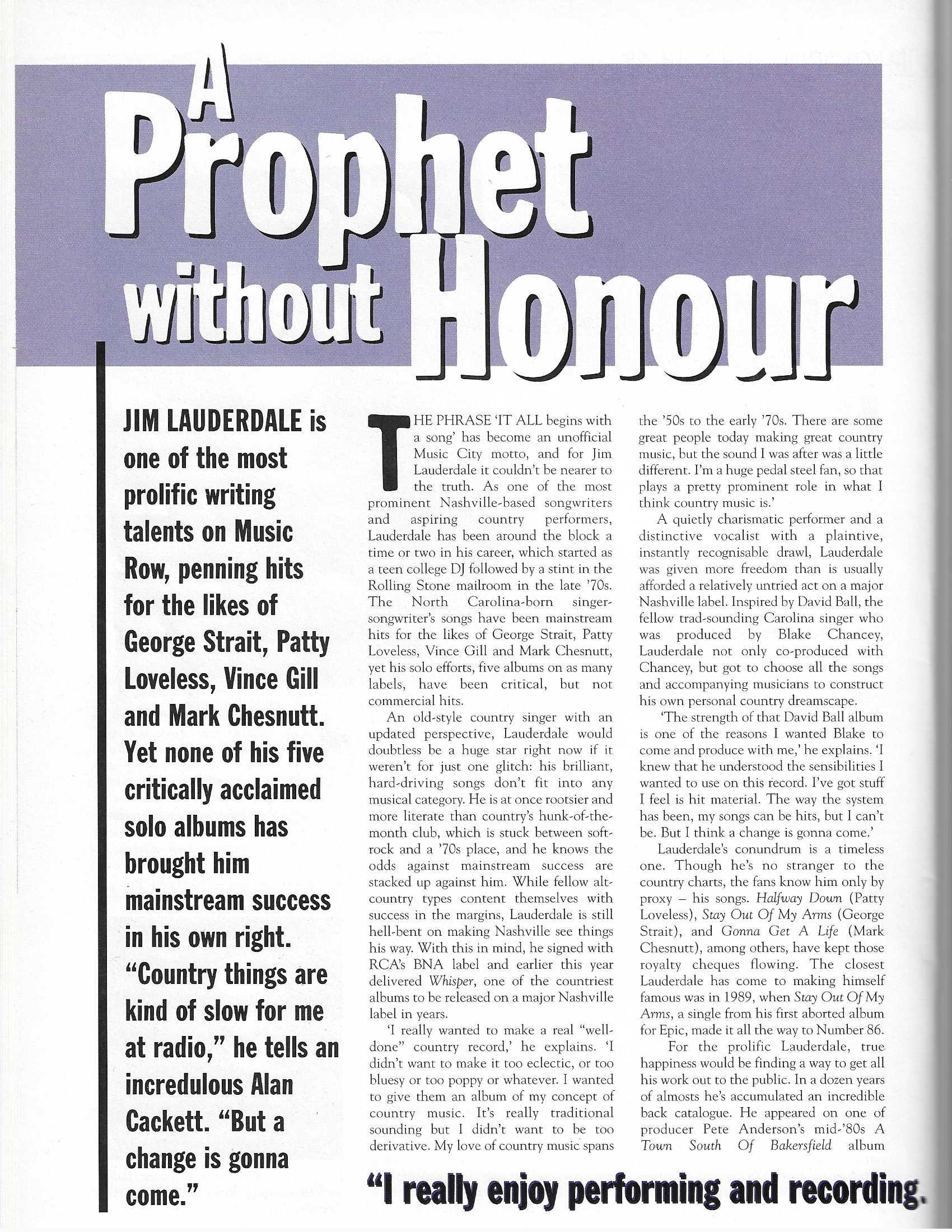

Jim Lauderdale is one of the most prolific writing talents on Music Row, penning hits for the likes of George Strait, Patty Loveless, Vince Gill and Mark Chesnutt. Yet none of his five critically acclaimed solo albums has brought him mainstream success in his own right. “Country things are kind of slow for me at radio,” he tells an incredulous Alan Cackett. “But a change is gonna come.”

The phrase ‘It all begins with a song’ has become an unofficial Music City motto, and for Jim Lauderdale it couldn’t be nearer to the truth. As one of the most prominent Nashville-based songwriters and aspiring country performers, Lauderdale has been around the block a time or two in his career, which started as a teen college DJ followed by a stint in the Rolling Stone mailroom in the late 1970s. The North Carolina-born singer-songwriter's songs have been mainstream hits for the likes of George Strait, Patty Loveless, Vince Gill and Mark Chesnutt, yet his solo effects, five albums on as many labels, have been critical, but not commercial hits.

The phrase ‘It all begins with a song’ has become an unofficial Music City motto, and for Jim Lauderdale it couldn’t be nearer to the truth. As one of the most prominent Nashville-based songwriters and aspiring country performers, Lauderdale has been around the block a time or two in his career, which started as a teen college DJ followed by a stint in the Rolling Stone mailroom in the late 1970s. The North Carolina-born singer-songwriter's songs have been mainstream hits for the likes of George Strait, Patty Loveless, Vince Gill and Mark Chesnutt, yet his solo effects, five albums on as many labels, have been critical, but not commercial hits.

An old-style country singer with an updated perspective, Lauderdale would doubtless be a huge star right now if it weren’t for just one glitch: his brilliant hard-driving songs don’t fit into any musical category. He is at once rootsier and more literate than country’s hunk-of-the-month club, which is stuck between soft-rock and a 1970s place, and he knows the odds against mainstream success are stacked up against him. While fellow alt-country types content themselves with success in the margins, Lauderdale is still hell-bent on making Nashville see things his way. With this in mind, he signed with RCA’s BNA label and earlier this year delivered WHISPER, one of the countriest albums to be released on a major Nashville label in years.

“I really wanted to make a real ‘well done’ country road,” he explains. “I didn’t want to make it too eclectic, or too bluesy or too poppy or whatever. I wanted to give them an album of my concept of country music. It’s really traditional sounding but I didn’t want to be too derivative. My love of country music spans the 1950s to the early 1970s. There are some great people today making great country music, but the sound I was after was a little different. I'm a huge pedal steel fan, so that plays a pretty prominent role in what I think country music is.”

A quietly charismatic performer and a distinctive vocalist with a plaintive, instantly recognisable drawl, Lauderdale was given more freedom than is usually afforded a relatively untried act on a major Nashville label. Inspired by David Ball, the fellow trad-sounding Carolina singer, who was produced by Blake Chancey, Lauderdale not only co-produced with Chancey, but got to choose all the songs and accompanying musicians to construct his own personal country dreamscape.

“The strength of that David Ball album is one of the reasons I wanted Blake to come and produce with me,” he explains. “I knew that he understood the sensibilities I wanted to use on his record. I've got stuff I feel is hit material. The way the system has been, my songs can be hits, but I can’t be. But I think a change is gonna come.”

Lauderdale’s conundrum is a timeless one. Though he’s no stranger to the country charts, the fans know him only by proxy—his songs. Halfway Down (Patty Loveless), Stay Out Of My Arms (George Strait), and Gonna Get A Life (Mark Chesnutt), among others, have kept those royalty cheques flowing. The closest Lauderdale has come to making himself famous was in 1989, when Stay Out Of My Arms, a single from his first aborted album for Epic, made it all the way to Number 86.

For the prolific Lauderdale, true happiness would be finding a way to get all his work out to the public. In a dozen years of almosts he’s accumulated an incredible back catalogue. He appeared on one of producer Pete Anderson’s mid-1980s A TOWN SOUTH OF BAKERFIELD album compilations (the first of which launched Dwight Yoakam’s career). A year later Anderson produced his ominously titled POINT OF NO RETURN, Epic released a couple of singles, but canned the album and dropped Lauderdale. There’s even a duet, The Tavern Choir with George Jones, lying in the Sony vaults somewhere, not to mention an album of unreleased material with bluegrass legend Roland White.

“It was supposed to be an album of George’s,” Lauderdale remembers. “A duet album called FRIENDS IN HIGH PLACES, but because my record didn’t come out, they didn’t include it. I know the fellas that are running Sony now, and I've been kind of reminded of that song. I talked to them about putting my unreleased album out, and they said it was an interesting idea, so maybe I could add that duet on there as a bonus cut.”

said it was an interesting idea, so maybe I could add that duet on there as a bonus cut.”

Lauderdale’s string of cuts as a writer began when Jann Browne cut Where The Sidewalk Ends in 1991. Vince Gill cut Sparkle the same year, then George Strait put Sidewalk and King Of Broken Hearts on the multi-million selling PURE COUNTRY soundtrack. Solidifying Lauderdale’s presence in Nashville’s writing circles, Strait also recorded five more Lauderdale tunes on his next three albums. In addition, Mandy Barnett, Doug Supernaw, Joy Lynn White, Kathy Mattea and a whole slew of bluegrass acts all included his songs on their albums.

The writing credits paved the way for further recording stints. In 1990 there was the Rodney Crowell-produced album PLANET OF LOVE—which sold critics, not records. His next pair of albums, both for Atlantic, were produced by southern California country-rock studio ace Dusty Wakeman, whose less polished style enabled Lauderdale to escape most of the strictures of the Nashville system. PRETTY CLOSE TO THE TRUTH, a masterpiece that links, rather than shifts styles, moves seamlessly from the two-beat stomps I’m On Your Side to the gorgeous Stax-sounding Why Do I Love You and the dusky pop of Divide And Conquer. For 1995’s EVERY SECOND COUNTS, Atlantic went straight to the adult pop marketplace, but the album lacked the light touch of its predecessor. When it didn’t sell, Atlantic lost patience.

His next set was the much-praised 1996-released PERSIMMONS for Upstart … all over the place, from straight country to garage-band rock to near-metal, and the most relaxed, rawest-sounding album he has made. But Upstart’s distance from Nashville, both geographically and stylistically, guaranteed the record’s death on country radio—and ultimately that’s what’s driven Lauderdale back into the fold.

Though it would be easier for him to drive into Nashville every day and write songs, not concerning himself with record label politics, marketing, touring or promotion, that ultimately, is not what Lauderdale is looking for. “I really enjoy performing and recording,” he concurs. “I’ll continue writing for other people, but it’s like having two careers. I need a stimulus from doing my own thing, to be able to write for other people. I think if I just wrote for other people, it might lose some of its edge.”

There is little doubt that he has learnt much from his first shot in the late 1980s and is fully prepared for all the pitfalls he might encounter. For the first time he has followed the Nashville label routine of radio promotion, and earlier this year spent a soul-draining, energy-sapping month out on the road touring radio stations to talk about WHISPER. Like so many before him, he encountered the false promises and two-faced approach of American radio, which really has little or no interest in the music, only in ratings and advertising revenues. While the DJs were enthusing about his music on air during the tour, they didn’t programme a single track after he left.

“I was warned that that would happen,” he says. “You get all this commitment from people who say: ‘Oh, I love your stuff. You can count on me.’ It’s hard to predict what will catch on. There’s a lot of competition out there. I'm pretty philosophical about it because I’ve had several record deals and some kinda half-hearted attempts before at getting me on the radio. Realistically, I’m one of a hundred new acts they’re trying to break. I don’t really consider myself a new act, but radio does.”

Co-writing for Lauderdale is still a relatively new experience, even though his first co-writing session was eight or nine years ago. During the ensuing years he has written with John Leventhal, Rodney Crowell, Frank Dycus, Buddy Miller, Melba Montgomery, John Scott Sherrill and Harlan Howard, but the majority of his writing is still done solo.

“I’m getting a little bit burned out on co-writing,” he explains. “I want to keep writing with Harlan Howard and a few other people, but sometimes it is too much of a commercial, assembly-line type thing with the goal of writing a hit song for somebody. At times I like that, building ideas, collaborating with somebody, but it’s hard to write with somebody you’ve never written with.”

He is sensible enough to know that it is hit songs for mainstream country acts that sustain his own recording career. Sometimes he has to weigh up whether to hang on to a song, or let it go. This happened while recording WHISPER, and rather reluctantly he let You Don’t Seem To Miss Me go to Patty Loveless, while George Strait cut We Really Shouldn’t Be Doing This for his latest album. In fact, the veteran Texas singer has cut more Jim Lauderdale songs than any other performer.

He is sensible enough to know that it is hit songs for mainstream country acts that sustain his own recording career. Sometimes he has to weigh up whether to hang on to a song, or let it go. This happened while recording WHISPER, and rather reluctantly he let You Don’t Seem To Miss Me go to Patty Loveless, while George Strait cut We Really Shouldn’t Be Doing This for his latest album. In fact, the veteran Texas singer has cut more Jim Lauderdale songs than any other performer.

As a songwriter, Jim Lauderdale has nothing to feel embarrassed about. Apart from the slew of country cuts, his songs have also been recorded by such diverse acts as Dave Edmunds, Etta James and John Mayall, and he is held in high esteem both by alt.country acts and British rockers such as Nick Lowe, for whom he has often opened shows.

Putting a handle on Jim Lauderdale’s music has always been a difficult proposition. The very eclecticism of his style has made acceptance of his own music somewhat elusive. Ultimately, his greatest virtue has also been his curse – he's too restlessly creative for mass marketing.

Is it rock, or is it country? Listen, it’s Jim Lauderdale—that should be enough.