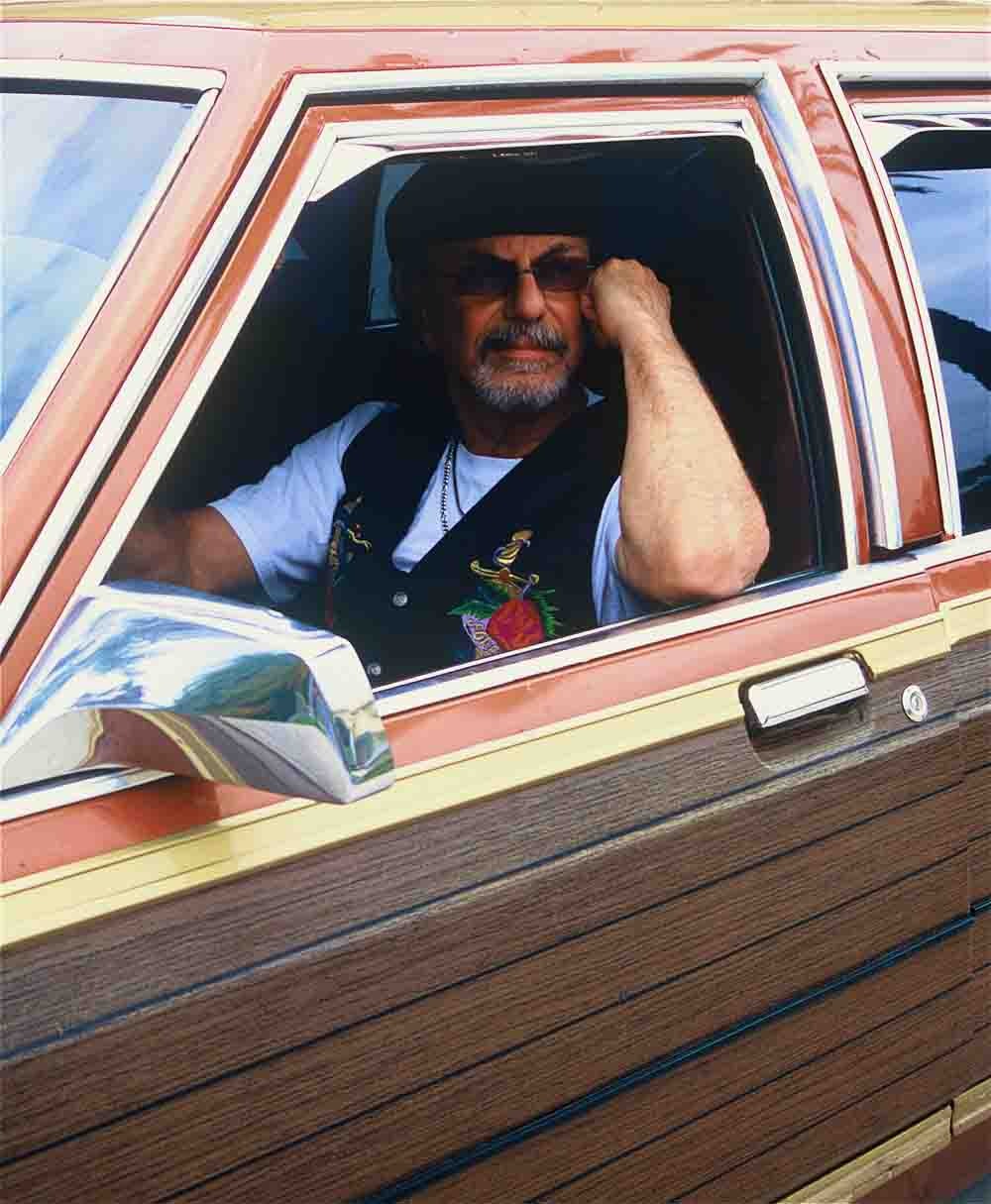

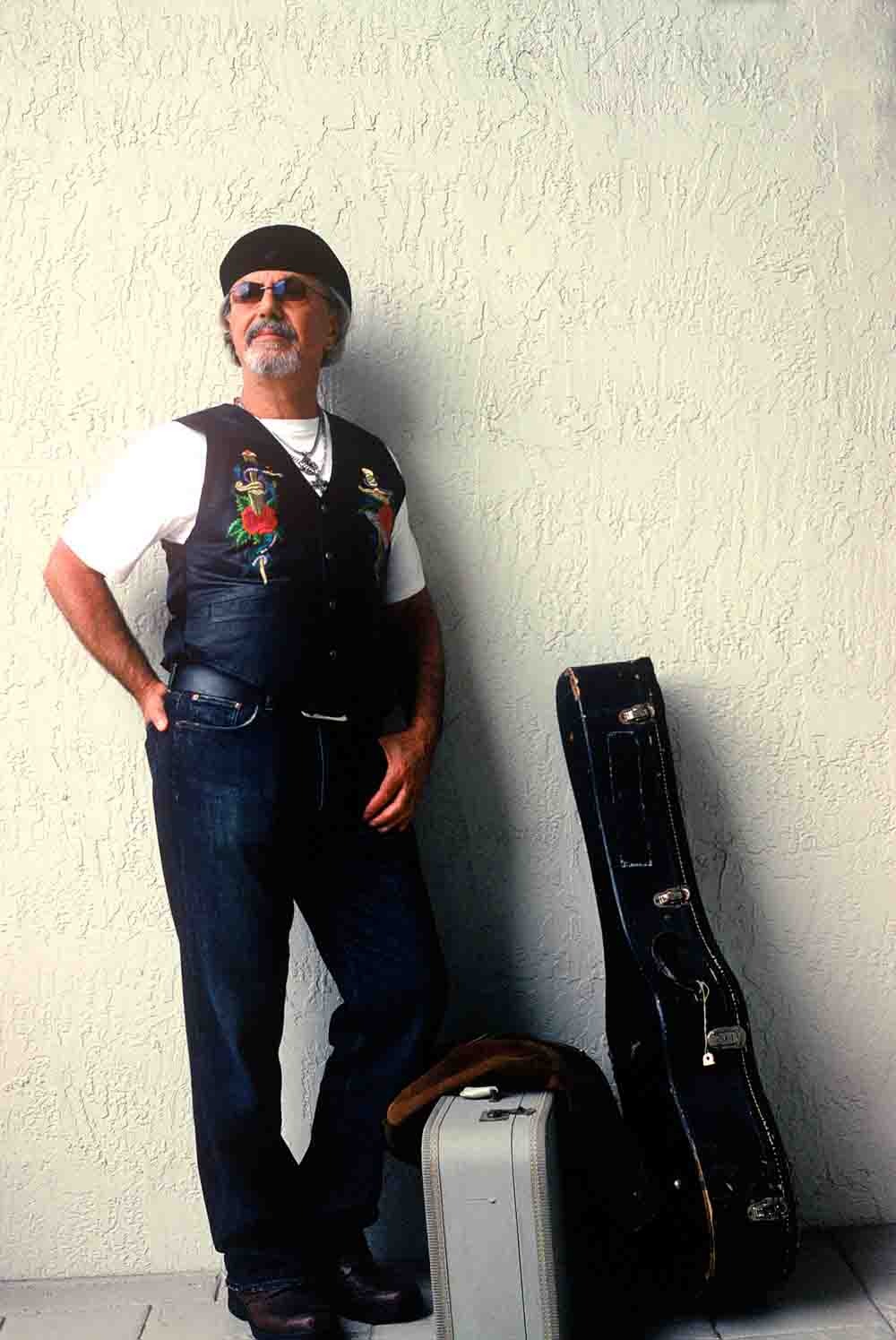

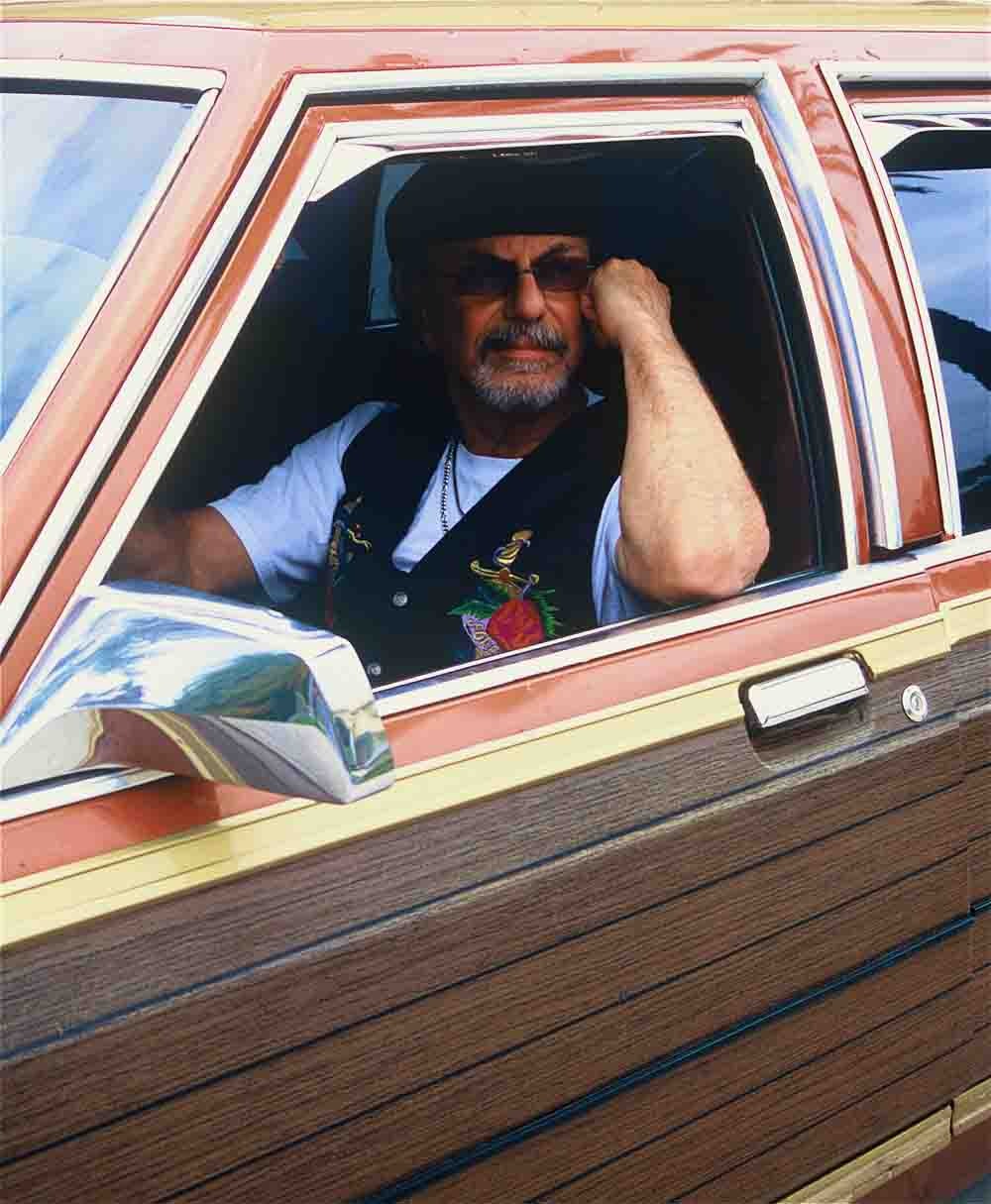

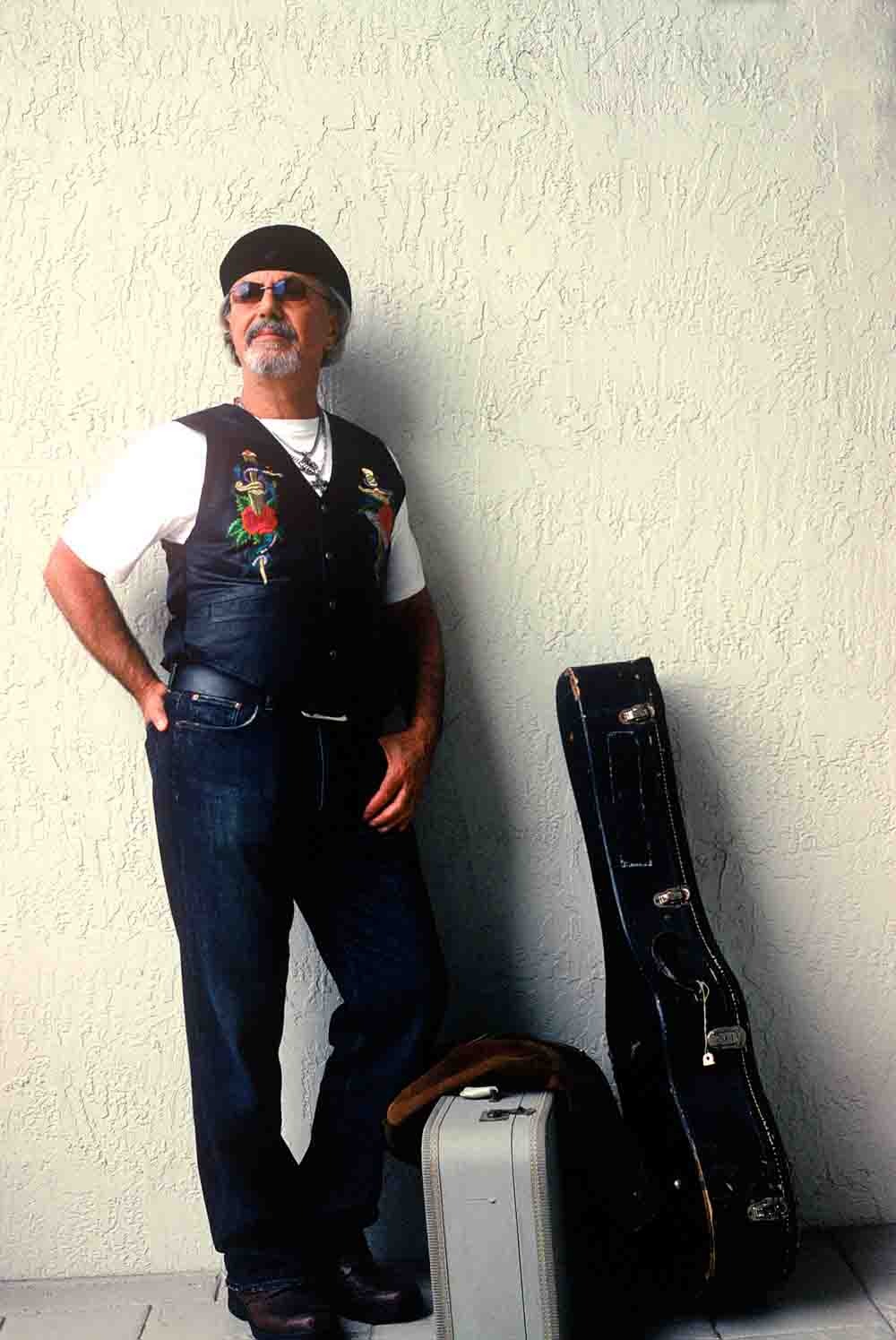

Dion

New York born and raised rock’n’roller Dion has been singing country tunes right alongside soul, blues, folk, gospel and rock his entire career. He grew up in the late 1940s and early 1950s listening to Hank Williams, alongside bluesmen like Howlin’ Wolf and Jimmy Reed. The first Dion & the Belmonts 1959 album included a cracking version of Tommy Collins’ You Better Not Do That and in 1963 he released his own distinctive rendition of Hank Williams’ Be Careful of Stones That You Throw.

New York born and raised rock’n’roller Dion has been singing country tunes right alongside soul, blues, folk, gospel and rock his entire career. He grew up in the late 1940s and early 1950s listening to Hank Williams, alongside bluesmen like Howlin’ Wolf and Jimmy Reed. The first Dion & the Belmonts 1959 album included a cracking version of Tommy Collins’ You Better Not Do That and in 1963 he released his own distinctive rendition of Hank Williams’ Be Careful of Stones That You Throw.

The most underrated vocal stylist of the whole rock’n’roll era, in recent years he has increasingly turned his hand to the blues and on his 2012 album, TANK FULL OF BLUES, he featured mainly his own self-penned blues songs, proving beyond doubt that singing the blues is as natural for Dion as breathing. With just his own trusty guitar and occasional percussion and bass from the Hurdy Gurdy Man aka Bob Guertin, Dion moves effortlessly from rural to country to urban blues in a seamless programme of the real thing. Having been a long time Dion fan it’s no surprise to me that he sounds right at home on every track. His soulful and plaintive voice commands attention on the 11-song exploration of the blues culture.

For me it was a dream came true when I got to talk to Dion about his career and passion for music in early 2012, some fifty years after I bought my first Dion record, the original version of Runaround Sue. Back in the early 1960s I had to import some of Dion’s records because they weren’t always readily available in the UK, despite the fact that he scored quite regularly in the British charts, and the that he came up against the inferior cover versions of his hits by the likes of Craig Douglas, Marty Wilde, Doug Sheldon, etc.

One of those LPs I imported was PRESENTING DION & THE BELMONTS released in America on Laurie Records in 1959. Amongst the doo-wop style hits was a version of Tommy Collins’ country classic You Better Not Do That, sung in Dion’s plaintive style with just the right amount of sly innuendo humour that the lyrics demanded. In short Dion had nailed the song perfectly as if he’d been raised on a diet of down-home country.

“Yeah I used to have fun with that song you know,” Dion recalled. “I was like fifteen years old when I sung that. It was like an outside song. I don’t know why I did that but I really knew Hank Williams’ music. I was very much a Hank Williams’ fan and Jimmy Reed that was my underpinning and probably everything that was the centre of me. I found that out recently well … I always knew I liked those guys, but I didn’t know how close to them I was. They were my centre and I connected with them more than what I thought. When I made BRONX IN BLUE in 2006, driving home with the CD—I recorded it in two days and it’s an album with me and my guitar and I just wanted to see that I could record the songs—and I was driving listening to the CD in the car and I said: ‘Oh my God, this is really me.’ I mean I don’t even have to think to do these songs, that’s how natural it was … that it wasn’t contrived at all.”

“I just kept following my heart and that’s why the new album is what it is. I thought of all the good material I grew up listening to and I just could spend the rest of my life interpreting these great songs like Tony Bennett or something. And then I was like I could write this stuff myself. I’d done an album called SON OF SKIP JAMES. And then I did an album called HEROES and I did all these songs that are important and I wanted to interpret and have fun with. Then and the thought came to me and as an artist I said: ‘I need to tell people who I am in this genre.’ So I put it out as it expresses my world vision … what’s happening in my mind, heart and soul. I thought I would express that.”

“I just kept following my heart and that’s why the new album is what it is. I thought of all the good material I grew up listening to and I just could spend the rest of my life interpreting these great songs like Tony Bennett or something. And then I was like I could write this stuff myself. I’d done an album called SON OF SKIP JAMES. And then I did an album called HEROES and I did all these songs that are important and I wanted to interpret and have fun with. Then and the thought came to me and as an artist I said: ‘I need to tell people who I am in this genre.’ So I put it out as it expresses my world vision … what’s happening in my mind, heart and soul. I thought I would express that.”

There had always been a blues feel to so much of Dion’s work. His solo singles for Laurie Records from the early 1960s like Love Came To Me, Lovers Who Wander, Sandy, (I Was) Born To Cry, Little Diane and of course The Wanderer and Runaround Sue were without doubt blues-infused rock’n’roll records. When he moved over to Columbia Records in 1962 he delved even more into a blues feel with fine revivals of the Drifters’ Ruby Baby and Drip Drop and his self-penned This Little Girl and Donna The Prima Donna. He also released distinctive renditions of Chuck Berry’s Johnny B Goode which was slowed down to a drifting country-blues interpretation and the blues classic I’m Your Hoochie Coochie Man. Much of Dion’s output for Columbia Records wasn’t released at the time, as he experimented more and more with blues material and didn’t reach the public ears until the 1997 2-CD set THE ROAD I’M ON.

He explained that his decision to carry on writing and making fresh music was inspired by noted rock journalist Dave Marsh. “I was with Dave Marsh and he said: ‘You’re the only guy from the 1950s who has remained relevant and creative.’ What the hell kind of remark is that? I looked at him and I said: ‘I think you’re giving me a little encouragement to go the wrong way.’ It was like that was a bit like a lightning bolt and I think that from then I just stepped under the spout where the inspiration comes out and I just couldn’t stop writing. That’s what led to TANK FULL OF BLUES. And some of the songs I wrote for it, when I wrote some of the lines, I thought: ‘How come nobody ever wrote this?’”

“Some lines really were funny because when I wrote: ‘I have a woman who wants me and a woman who wants me gone’ and I thought: ‘How come no one ever wrote that line.’ These lines are coming along and I’m thinking this is crazy. Honestly, I was amazing myself and I think I feel more relevant now than what I did when I was making the hit records. I got to write some good lines and have a great memory and I love life so there we go.”

If you look back over Dion’s career, more than any other artist out there, he has consistently re-invented himself both on a musical level and in his personal life. In the late 1950s he was heavily into street-corner doo-wop with the Belmonts. In the early 1960s he was the swaggering New York punk boasting triumphantly that he had ‘Rosie on his chest.’ Then came his blues phase of 1962-65 which pre-dated the British blues boom instigated by The Rolling Stones, The Animals and Alexis Korner.

Failing to connect on a commercial level he then moved into a folk-styled singer-songwriter period years before the rise of James Taylor, Don McLean, Dan Fogelberg and so on. In 1968 he scored with the original and definitive version of Abraham, Martin and John and went on to release a series of critically acclaimed singer-songwriter albums for Warner Brothers. In the early 1980s he became a born-again Christian and recorded mainly contemporary Christian music, much of it self-written. In 1984 he won the Dove Award (Christian Music Award) for the album I PUT AWAY MY IDOLS and was also nominated for a Grammy Award, best male Gospel performance, for the same album.

Five years later came what I consider to be the definitive Dion album, YO FRANKIE, released on Arista Records. The album followed his induction into the Rock’n’Roll Hall of Fame and the endorsements that he received from such then contemporary rock musicians as Bruce Springtseen, Lou Reed and others. The album was produced by Dave Edmunds and featured such guest singers and musicians as Paul Simon, Lou Reed, k d lang, Patty Smyth and Bryan Adams.

“If you were sitting with me and I sang a song from each of those different eras or whatever, it all sounds like Dion music. It’s really weird how much a producer like Steve Barri or Phil Spector, how different the songs come out with the window trimmings, you know it sounds completely different. Even if I sing a gospel song and I sing a blues song it pretty much almost sounds like it sounds like the same when I do it in a room with a guitar. It’s a funny thing.”

I’ve only seen Dion sing in a concert setting once and that was way back in 1962/63 when he was part of a package show playing one-nighters across the UK, usually appearing in cinemas with the same band providing the accompaniment for all the acts on the show. I think that Dion only got to sing five or six songs, but for me he stole the show with his professionalism and the cool way he handled himself. So I asked if he had any plans to tour behind his latest album.

“I have no idea and I couldn’t care less … well I do care. I just do it and if people like it they like it. I can’t control that. I’m enjoying it. That was always the difference between rock’n’roll and show business. Show business is like: ‘Hey having a good time … I hope you’re enjoying yourself.’ Rock’n’roll is like I don’t care how you feel if you wanna come along then come along and if not please leave. My opinion is I wanna take people on a trip and a good trip, but if they don’t wanna come then I’ll see you later.”

What I’ve always liked about Dion he’s always made his music very much on his own terms and that no-nonsense attitude always comes across in his recordings. Even now, in his early seventies there’s still that same kind of punk-ish attitude that he had when he was a teenager.

“I think it’s good because I learned from my mother, well actually not my mother. I think I learned it from one of my friends. I think it was at a family gathering where I heard it, but he said: ‘It’s a wonderful thing to help people and serve people and you know be about helping your fellow human beings. Being a service is a wonderful thing so long as you do it on your terms it’s very fulfilling. To do it on other people’s terms is disastrous, especially when they start dictating.”

“I’ve been in a recovery programme for like 44 years and I haven’t had trouble with drink and drugs, so I like helping people getting them out of addiction. But if they start dictating the terms of their recovery, well, I say if you happen to know better, then go and do it. But if they want to recover and they want to know how I did it, then fine I’ll go to hell for you. But if they want to do it by themselves then they can go. So I do it on my terms and I think it’s the only way to do it. You know what, people who do it on other people’s terms it leads to a resentment such as: ‘I did all this for you and you don’t even care.’ Do you understand what I’m saying?”

This is what comes through in Dion’s music. Even when he worked in the studio with people that weren’t totally conducive to his talent or recording songs that weren’t really the ‘real’ Dion. Yet despite that he was always able to put his own stamp on the songs and make them very much his own.

“Well, I try. In the early days and when I started out, like when I grew up there was no rock’n’roll. So when I was at Columbia Records it was like they were so trying to make me do stuff, so I was like: ‘Well I will do that if you let me do this.’ When I was a kid, I was a little more insecure so I did one of their songs and then they allowed me do one of my songs. I’ll do a range of songs if you want me to, but it was like one for you, one for me, and I had good music sensibility … well I thought so.”

One of the songs that Dion cut which was very much ‘one for him’ was Be Careful Of Stones That You Throw, an old Luke the Drifter song originally written and recorded by Hank Williams. It was a single for Columbia in 1963 and against all the odds became an American top 40 pop hit.

“I could recite that song to you right now, but I never liked that record because of the production. It wasn’t recorded in the way that I would of recorded it. I haven’t heard it in God knows, years! But I remember it being totally washed out. It was like you wanna record a guitar and next they say well let’s put a flute on there. But I will tell you something about that song, it taught me how to live and actually learn how to live. I got some principles through Hank Williams. Even though he didn’t know how to live himself he was honest in his music, certainly, that stands up for me, you could write that today in my community where I live.”

Hank Williams had that rare ability to write simple but effective 2 or 3 minute songs that in a few short verses summed up real life situations. There was no sugar coating it was quite simply life as he saw it, and the sentiments and the morals of those songs are still very relevant today.

“ Well you know what I loved about that, I’ve always had this sense that I could feel the person on the other side of the music. I could tell if they were lying to me or if they were real. I don’t know what that is, it doesn’t matter what kind of music, but I could feel the person whowas sharing what was at the centre of their thing. I knew that when I was thirteen years old, but I was eleven years old when I heard Hank Williams and he was so committed to every line he sang … at the end of each line he almost ripped the words off the page with his teeth and it sounded like he dug into it and he ripped a bite out of it to me. That’s how committed he was, so I was always committed to that kind of music.”

Well you know what I loved about that, I’ve always had this sense that I could feel the person on the other side of the music. I could tell if they were lying to me or if they were real. I don’t know what that is, it doesn’t matter what kind of music, but I could feel the person whowas sharing what was at the centre of their thing. I knew that when I was thirteen years old, but I was eleven years old when I heard Hank Williams and he was so committed to every line he sang … at the end of each line he almost ripped the words off the page with his teeth and it sounded like he dug into it and he ripped a bite out of it to me. That’s how committed he was, so I was always committed to that kind of music.”

“I heard, Jimmy Reed of course and Muddy Waters and Little Richard and there’s a commitment there and even if he [Hank Williams] was copying a record he really dug into it. So early on I just always grabbed onto that and when I went to Columbia Records, I had sold millions of records and to have them [Columbia label head John Hammond] play me Robert Johnson in 1961 and I heard him in that way. I knew that my friends would say what the hell you listening to that for … but I knew there was something there. I looked up to that kind of music and I was told that Robert Johnson sold 25,000 records and that was a lot back then.”

Unbeknown to most music fans when Dion was recording for Columbia in the early 1960s he was way ahead of acts like The Rolling Stones, The Animals and The Yardbirds who have all been given the credit for re-inventing the blues. Because of his hits like A Teenager In Love, Lonely Teenager and I Wonder Why, he was all too often dismissed as just another teen idol and placed alongside such lightweights as Bobby Rydell and Fabian, when in fact he should be held in the same esteem as Buddy Holly, Eddie Cochran, Chuck Berry and Fats Domino.

“Well, maybe I was, but they [the British groups] heard stuff and they really got it right and they were a little more removed from it, whereas I couldn’t go to the Apollo Theatre and sing ‘like a black person’ like Mick Jagger does. Well that’s what I thought, but they were a little more removed but they got it right. I never called it a British Invasion, I call it the British infusion. I think the people that founded early rock’n’roll, some of them never grew and they stopped in 1963. But the British guys they were in tune with the roots and so was I. I was onboard with that whole thing … I heard it!”

It’s a well-documented fact that during the late 1950s and the first half of the 1960s that Dion was a heroin addict. With the help of his wife Susan and his wholefamily and his own perseverance he kicked the habit and by the early 1970s was sounding vocally at the top of his game. He recorded a series of introspective singer-songwriter albums that remain amongst some of my all-time favourite albums. Though the albums were not big-sellers I got the impression from Dion’s own songs on those albums that both mentally and physically he was in a good place at that time.

“I was! It seemed like the obsession to drink and drugs was removed from me right before I recorded with them, and that was a good place. It put me on a road of looking to get high on life and not drinking and drugs. So when I recorded those albums I was almost like ten years into it like clean and sober so to speak and I was healthy and vibrant and I felt good. I felt good creatively, healthily and it was good.”

Though he was no longer a successful chart act, Dion’s talent as a songwriter and his interpretative skills were at an all-time high. In 1975 he recorded the Phil Spector-produced BORN TO BE WITH YOU. The album was a commercial failure, but has been subsequently widely acclaimed as one of the masterpiece albums of the 1970s. Three years later came RETURN OF THE WANDERER, which drew on many of his teenage influences but was yet another commercial failure. He recorded a follow-up album, FIRE IN THE NIGHT, which remained unissued until 1990.

“The follow up, we were trudging. It was so hard it was like almost torture. But the first one, was when we were just on a roll and I was having fun writing songs, the band was new and then these two guys came into our lives and they tried to control the recordings so much that things sometimes aren’t so good. It was lifeless, it didn’t have that spark, I dunno it was too much of a struggle that it never got off the ground. In the spirit the songs were good but I don’t think we had it, that’s my personal opinion on the way I remember those sessions—it was hard!”

“I have an album here with 23 songs that the band and I went in and recorded to flesh out … some of the songs that we had for FIRE IN THE NIGHT. It’s an incredible album it should have been released, but I just have it on a CD. But when we went into the studio to actually do it, they were trying to control it so much and you can’t do that. They sucked the life out of it, but originally there were some great songs. We went through these songs in the studio one after the other, we weren’t looking to get them you know right, we just wanted to express them and the tape that I have here … the CD of that session is incredible. We did like 23 songs in one day just to see what we had, incredible! We didn’t release that, but the album that came out was just too controlled.”

Then we moved on to YO FRANKIE, but surprisingly Dion didn’t share my enthusiasm for an album which I feel is the pinnacle of his recording career.

“Well, it was difficult because again I did it on his terms so it wasn’t like TANK FULL OF BLUES, where it had been on my time and my production. But I enjoyed being with Dave and Terry Williams and oh my god that was fun. I gotta say, Dave Edmunds what can I tell you? I love being around these guys, so it was a lot of fun. I kind of look up to them as musicians, I guess we’ve been learning from each other when it comes down to it and they’re good guys. It was a very positive atmosphere to be around.”

Like many of the stars of the 1950s and 1960s, Dion still gets out there and does the rock’n’roll revival shows, but again he does these very much on his own terms and adds so much extra to his original hits—a contemporary edge that takes nothing away from the original vibe.

“It’s a funny thing, from the very beginning when I toured with Buddy Holly, it’s funny how he never had a guitar solo on any of his records, but in person the songs would last four or five minutes and that’s what I do today. I’ve always done that, add a little more than just the record. Sometimes I’ll do Teenager In Love for people because it has a life of its own, I’ll do a couple of bridges and some solos in it. The same for Runaround Sue, I Wonder Why, Ruby Baby. I kind of stretch them out to five minutes make them fun. It’s fun to lengthen them and people don’t mind it—they enjoy it. The records were too short and were geared for radio.”

Alan Cackett

New York born and raised rock’n’roller Dion has been singing country tunes right alongside soul, blues, folk, gospel and rock his entire career. He grew up in the late 1940s and early 1950s listening to Hank Williams, alongside bluesmen like Howlin’ Wolf and Jimmy Reed. The first Dion & the Belmonts 1959 album included a cracking version of Tommy Collins’ You Better Not Do That and in 1963 he released his own distinctive rendition of Hank Williams’ Be Careful of Stones That You Throw.

New York born and raised rock’n’roller Dion has been singing country tunes right alongside soul, blues, folk, gospel and rock his entire career. He grew up in the late 1940s and early 1950s listening to Hank Williams, alongside bluesmen like Howlin’ Wolf and Jimmy Reed. The first Dion & the Belmonts 1959 album included a cracking version of Tommy Collins’ You Better Not Do That and in 1963 he released his own distinctive rendition of Hank Williams’ Be Careful of Stones That You Throw. The most underrated vocal stylist of the whole rock’n’roll era, in recent years he has increasingly turned his hand to the blues and on his 2012 album, TANK FULL OF BLUES, he featured mainly his own self-penned blues songs, proving beyond doubt that singing the blues is as natural for Dion as breathing. With just his own trusty guitar and occasional percussion and bass from the Hurdy Gurdy Man aka Bob Guertin, Dion moves effortlessly from rural to country to urban blues in a seamless programme of the real thing. Having been a long time Dion fan it’s no surprise to me that he sounds right at home on every track. His soulful and plaintive voice commands attention on the 11-song exploration of the blues culture.

For me it was a dream came true when I got to talk to Dion about his career and passion for music in early 2012, some fifty years after I bought my first Dion record, the original version of Runaround Sue. Back in the early 1960s I had to import some of Dion’s records because they weren’t always readily available in the UK, despite the fact that he scored quite regularly in the British charts, and the that he came up against the inferior cover versions of his hits by the likes of Craig Douglas, Marty Wilde, Doug Sheldon, etc.

One of those LPs I imported was PRESENTING DION & THE BELMONTS released in America on Laurie Records in 1959. Amongst the doo-wop style hits was a version of Tommy Collins’ country classic You Better Not Do That, sung in Dion’s plaintive style with just the right amount of sly innuendo humour that the lyrics demanded. In short Dion had nailed the song perfectly as if he’d been raised on a diet of down-home country.

“Yeah I used to have fun with that song you know,” Dion recalled. “I was like fifteen years old when I sung that. It was like an outside song. I don’t know why I did that but I really knew Hank Williams’ music. I was very much a Hank Williams’ fan and Jimmy Reed that was my underpinning and probably everything that was the centre of me. I found that out recently well … I always knew I liked those guys, but I didn’t know how close to them I was. They were my centre and I connected with them more than what I thought. When I made BRONX IN BLUE in 2006, driving home with the CD—I recorded it in two days and it’s an album with me and my guitar and I just wanted to see that I could record the songs—and I was driving listening to the CD in the car and I said: ‘Oh my God, this is really me.’ I mean I don’t even have to think to do these songs, that’s how natural it was … that it wasn’t contrived at all.”

“I just kept following my heart and that’s why the new album is what it is. I thought of all the good material I grew up listening to and I just could spend the rest of my life interpreting these great songs like Tony Bennett or something. And then I was like I could write this stuff myself. I’d done an album called SON OF SKIP JAMES. And then I did an album called HEROES and I did all these songs that are important and I wanted to interpret and have fun with. Then and the thought came to me and as an artist I said: ‘I need to tell people who I am in this genre.’ So I put it out as it expresses my world vision … what’s happening in my mind, heart and soul. I thought I would express that.”

“I just kept following my heart and that’s why the new album is what it is. I thought of all the good material I grew up listening to and I just could spend the rest of my life interpreting these great songs like Tony Bennett or something. And then I was like I could write this stuff myself. I’d done an album called SON OF SKIP JAMES. And then I did an album called HEROES and I did all these songs that are important and I wanted to interpret and have fun with. Then and the thought came to me and as an artist I said: ‘I need to tell people who I am in this genre.’ So I put it out as it expresses my world vision … what’s happening in my mind, heart and soul. I thought I would express that.”There had always been a blues feel to so much of Dion’s work. His solo singles for Laurie Records from the early 1960s like Love Came To Me, Lovers Who Wander, Sandy, (I Was) Born To Cry, Little Diane and of course The Wanderer and Runaround Sue were without doubt blues-infused rock’n’roll records. When he moved over to Columbia Records in 1962 he delved even more into a blues feel with fine revivals of the Drifters’ Ruby Baby and Drip Drop and his self-penned This Little Girl and Donna The Prima Donna. He also released distinctive renditions of Chuck Berry’s Johnny B Goode which was slowed down to a drifting country-blues interpretation and the blues classic I’m Your Hoochie Coochie Man. Much of Dion’s output for Columbia Records wasn’t released at the time, as he experimented more and more with blues material and didn’t reach the public ears until the 1997 2-CD set THE ROAD I’M ON.

He explained that his decision to carry on writing and making fresh music was inspired by noted rock journalist Dave Marsh. “I was with Dave Marsh and he said: ‘You’re the only guy from the 1950s who has remained relevant and creative.’ What the hell kind of remark is that? I looked at him and I said: ‘I think you’re giving me a little encouragement to go the wrong way.’ It was like that was a bit like a lightning bolt and I think that from then I just stepped under the spout where the inspiration comes out and I just couldn’t stop writing. That’s what led to TANK FULL OF BLUES. And some of the songs I wrote for it, when I wrote some of the lines, I thought: ‘How come nobody ever wrote this?’”

“Some lines really were funny because when I wrote: ‘I have a woman who wants me and a woman who wants me gone’ and I thought: ‘How come no one ever wrote that line.’ These lines are coming along and I’m thinking this is crazy. Honestly, I was amazing myself and I think I feel more relevant now than what I did when I was making the hit records. I got to write some good lines and have a great memory and I love life so there we go.”

If you look back over Dion’s career, more than any other artist out there, he has consistently re-invented himself both on a musical level and in his personal life. In the late 1950s he was heavily into street-corner doo-wop with the Belmonts. In the early 1960s he was the swaggering New York punk boasting triumphantly that he had ‘Rosie on his chest.’ Then came his blues phase of 1962-65 which pre-dated the British blues boom instigated by The Rolling Stones, The Animals and Alexis Korner.

Failing to connect on a commercial level he then moved into a folk-styled singer-songwriter period years before the rise of James Taylor, Don McLean, Dan Fogelberg and so on. In 1968 he scored with the original and definitive version of Abraham, Martin and John and went on to release a series of critically acclaimed singer-songwriter albums for Warner Brothers. In the early 1980s he became a born-again Christian and recorded mainly contemporary Christian music, much of it self-written. In 1984 he won the Dove Award (Christian Music Award) for the album I PUT AWAY MY IDOLS and was also nominated for a Grammy Award, best male Gospel performance, for the same album.

Five years later came what I consider to be the definitive Dion album, YO FRANKIE, released on Arista Records. The album followed his induction into the Rock’n’Roll Hall of Fame and the endorsements that he received from such then contemporary rock musicians as Bruce Springtseen, Lou Reed and others. The album was produced by Dave Edmunds and featured such guest singers and musicians as Paul Simon, Lou Reed, k d lang, Patty Smyth and Bryan Adams.

“If you were sitting with me and I sang a song from each of those different eras or whatever, it all sounds like Dion music. It’s really weird how much a producer like Steve Barri or Phil Spector, how different the songs come out with the window trimmings, you know it sounds completely different. Even if I sing a gospel song and I sing a blues song it pretty much almost sounds like it sounds like the same when I do it in a room with a guitar. It’s a funny thing.”

I’ve only seen Dion sing in a concert setting once and that was way back in 1962/63 when he was part of a package show playing one-nighters across the UK, usually appearing in cinemas with the same band providing the accompaniment for all the acts on the show. I think that Dion only got to sing five or six songs, but for me he stole the show with his professionalism and the cool way he handled himself. So I asked if he had any plans to tour behind his latest album.

“I have no idea and I couldn’t care less … well I do care. I just do it and if people like it they like it. I can’t control that. I’m enjoying it. That was always the difference between rock’n’roll and show business. Show business is like: ‘Hey having a good time … I hope you’re enjoying yourself.’ Rock’n’roll is like I don’t care how you feel if you wanna come along then come along and if not please leave. My opinion is I wanna take people on a trip and a good trip, but if they don’t wanna come then I’ll see you later.”

What I’ve always liked about Dion he’s always made his music very much on his own terms and that no-nonsense attitude always comes across in his recordings. Even now, in his early seventies there’s still that same kind of punk-ish attitude that he had when he was a teenager.

“I think it’s good because I learned from my mother, well actually not my mother. I think I learned it from one of my friends. I think it was at a family gathering where I heard it, but he said: ‘It’s a wonderful thing to help people and serve people and you know be about helping your fellow human beings. Being a service is a wonderful thing so long as you do it on your terms it’s very fulfilling. To do it on other people’s terms is disastrous, especially when they start dictating.”

“I’ve been in a recovery programme for like 44 years and I haven’t had trouble with drink and drugs, so I like helping people getting them out of addiction. But if they start dictating the terms of their recovery, well, I say if you happen to know better, then go and do it. But if they want to recover and they want to know how I did it, then fine I’ll go to hell for you. But if they want to do it by themselves then they can go. So I do it on my terms and I think it’s the only way to do it. You know what, people who do it on other people’s terms it leads to a resentment such as: ‘I did all this for you and you don’t even care.’ Do you understand what I’m saying?”

This is what comes through in Dion’s music. Even when he worked in the studio with people that weren’t totally conducive to his talent or recording songs that weren’t really the ‘real’ Dion. Yet despite that he was always able to put his own stamp on the songs and make them very much his own.

“Well, I try. In the early days and when I started out, like when I grew up there was no rock’n’roll. So when I was at Columbia Records it was like they were so trying to make me do stuff, so I was like: ‘Well I will do that if you let me do this.’ When I was a kid, I was a little more insecure so I did one of their songs and then they allowed me do one of my songs. I’ll do a range of songs if you want me to, but it was like one for you, one for me, and I had good music sensibility … well I thought so.”

One of the songs that Dion cut which was very much ‘one for him’ was Be Careful Of Stones That You Throw, an old Luke the Drifter song originally written and recorded by Hank Williams. It was a single for Columbia in 1963 and against all the odds became an American top 40 pop hit.

“I could recite that song to you right now, but I never liked that record because of the production. It wasn’t recorded in the way that I would of recorded it. I haven’t heard it in God knows, years! But I remember it being totally washed out. It was like you wanna record a guitar and next they say well let’s put a flute on there. But I will tell you something about that song, it taught me how to live and actually learn how to live. I got some principles through Hank Williams. Even though he didn’t know how to live himself he was honest in his music, certainly, that stands up for me, you could write that today in my community where I live.”

Hank Williams had that rare ability to write simple but effective 2 or 3 minute songs that in a few short verses summed up real life situations. There was no sugar coating it was quite simply life as he saw it, and the sentiments and the morals of those songs are still very relevant today.

“

Well you know what I loved about that, I’ve always had this sense that I could feel the person on the other side of the music. I could tell if they were lying to me or if they were real. I don’t know what that is, it doesn’t matter what kind of music, but I could feel the person whowas sharing what was at the centre of their thing. I knew that when I was thirteen years old, but I was eleven years old when I heard Hank Williams and he was so committed to every line he sang … at the end of each line he almost ripped the words off the page with his teeth and it sounded like he dug into it and he ripped a bite out of it to me. That’s how committed he was, so I was always committed to that kind of music.”

Well you know what I loved about that, I’ve always had this sense that I could feel the person on the other side of the music. I could tell if they were lying to me or if they were real. I don’t know what that is, it doesn’t matter what kind of music, but I could feel the person whowas sharing what was at the centre of their thing. I knew that when I was thirteen years old, but I was eleven years old when I heard Hank Williams and he was so committed to every line he sang … at the end of each line he almost ripped the words off the page with his teeth and it sounded like he dug into it and he ripped a bite out of it to me. That’s how committed he was, so I was always committed to that kind of music.”“I heard, Jimmy Reed of course and Muddy Waters and Little Richard and there’s a commitment there and even if he [Hank Williams] was copying a record he really dug into it. So early on I just always grabbed onto that and when I went to Columbia Records, I had sold millions of records and to have them [Columbia label head John Hammond] play me Robert Johnson in 1961 and I heard him in that way. I knew that my friends would say what the hell you listening to that for … but I knew there was something there. I looked up to that kind of music and I was told that Robert Johnson sold 25,000 records and that was a lot back then.”

Unbeknown to most music fans when Dion was recording for Columbia in the early 1960s he was way ahead of acts like The Rolling Stones, The Animals and The Yardbirds who have all been given the credit for re-inventing the blues. Because of his hits like A Teenager In Love, Lonely Teenager and I Wonder Why, he was all too often dismissed as just another teen idol and placed alongside such lightweights as Bobby Rydell and Fabian, when in fact he should be held in the same esteem as Buddy Holly, Eddie Cochran, Chuck Berry and Fats Domino.

“Well, maybe I was, but they [the British groups] heard stuff and they really got it right and they were a little more removed from it, whereas I couldn’t go to the Apollo Theatre and sing ‘like a black person’ like Mick Jagger does. Well that’s what I thought, but they were a little more removed but they got it right. I never called it a British Invasion, I call it the British infusion. I think the people that founded early rock’n’roll, some of them never grew and they stopped in 1963. But the British guys they were in tune with the roots and so was I. I was onboard with that whole thing … I heard it!”

It’s a well-documented fact that during the late 1950s and the first half of the 1960s that Dion was a heroin addict. With the help of his wife Susan and his wholefamily and his own perseverance he kicked the habit and by the early 1970s was sounding vocally at the top of his game. He recorded a series of introspective singer-songwriter albums that remain amongst some of my all-time favourite albums. Though the albums were not big-sellers I got the impression from Dion’s own songs on those albums that both mentally and physically he was in a good place at that time.

“I was! It seemed like the obsession to drink and drugs was removed from me right before I recorded with them, and that was a good place. It put me on a road of looking to get high on life and not drinking and drugs. So when I recorded those albums I was almost like ten years into it like clean and sober so to speak and I was healthy and vibrant and I felt good. I felt good creatively, healthily and it was good.”

Though he was no longer a successful chart act, Dion’s talent as a songwriter and his interpretative skills were at an all-time high. In 1975 he recorded the Phil Spector-produced BORN TO BE WITH YOU. The album was a commercial failure, but has been subsequently widely acclaimed as one of the masterpiece albums of the 1970s. Three years later came RETURN OF THE WANDERER, which drew on many of his teenage influences but was yet another commercial failure. He recorded a follow-up album, FIRE IN THE NIGHT, which remained unissued until 1990.

“The follow up, we were trudging. It was so hard it was like almost torture. But the first one, was when we were just on a roll and I was having fun writing songs, the band was new and then these two guys came into our lives and they tried to control the recordings so much that things sometimes aren’t so good. It was lifeless, it didn’t have that spark, I dunno it was too much of a struggle that it never got off the ground. In the spirit the songs were good but I don’t think we had it, that’s my personal opinion on the way I remember those sessions—it was hard!”

“I have an album here with 23 songs that the band and I went in and recorded to flesh out … some of the songs that we had for FIRE IN THE NIGHT. It’s an incredible album it should have been released, but I just have it on a CD. But when we went into the studio to actually do it, they were trying to control it so much and you can’t do that. They sucked the life out of it, but originally there were some great songs. We went through these songs in the studio one after the other, we weren’t looking to get them you know right, we just wanted to express them and the tape that I have here … the CD of that session is incredible. We did like 23 songs in one day just to see what we had, incredible! We didn’t release that, but the album that came out was just too controlled.”

Then we moved on to YO FRANKIE, but surprisingly Dion didn’t share my enthusiasm for an album which I feel is the pinnacle of his recording career.

“Well, it was difficult because again I did it on his terms so it wasn’t like TANK FULL OF BLUES, where it had been on my time and my production. But I enjoyed being with Dave and Terry Williams and oh my god that was fun. I gotta say, Dave Edmunds what can I tell you? I love being around these guys, so it was a lot of fun. I kind of look up to them as musicians, I guess we’ve been learning from each other when it comes down to it and they’re good guys. It was a very positive atmosphere to be around.”

Like many of the stars of the 1950s and 1960s, Dion still gets out there and does the rock’n’roll revival shows, but again he does these very much on his own terms and adds so much extra to his original hits—a contemporary edge that takes nothing away from the original vibe.

“It’s a funny thing, from the very beginning when I toured with Buddy Holly, it’s funny how he never had a guitar solo on any of his records, but in person the songs would last four or five minutes and that’s what I do today. I’ve always done that, add a little more than just the record. Sometimes I’ll do Teenager In Love for people because it has a life of its own, I’ll do a couple of bridges and some solos in it. The same for Runaround Sue, I Wonder Why, Ruby Baby. I kind of stretch them out to five minutes make them fun. It’s fun to lengthen them and people don’t mind it—they enjoy it. The records were too short and were geared for radio.”

Alan Cackett