Contemporary Cowboy Music

First published in Country Music People, September 1974

Cowboy Music is not dead! It’s alive and kicking, but perhaps not easily recognised by those who were brought up on the idea that cowboy music is all about horses, Tex Ritter, Gene Autry and Roy Rogers. There’s a new type of cowboy music, it deals with the 1970s but the basic freedom and romantic air that abounded in the songs of the cowboy of yesterday is all there today.

You cannot really pick a leader of the cowboy scene today, just like in the past, it has emerged in several centres, but has come together as an entirely separate entity of country music. As a natural extension of the old cowboy scene, it’s perfect, but don’t expect the lyrics or sounds to be quite the same. In order for the music to exist in the 1970s it had to be current and acceptable—people like Waylon Jennings, The Eagles, Billy Joe Shaver, Willie Nelson, The New Riders of the Purple Sage, John Stewart and others are the ones who are laying down the songs and the styles. All of them in their own way are re-enacting the golden days of cowboy music.

Many of the contemporary cowboys hail from Texas. Like Waylon Jennings—a man who has lived—there is a suffering on his face, not the drooping miserable look of a failure. No, his face, chipped and worn about the eyes and cheekbones, is a result of a life being knocked down repeatedly, not so much physically, but more of the outward expressions of internal weariness. On the sleeve notes of his album LADIES LOVE OUTLAW, Robert Hilburn calls Jennings ‘A ragged, exciting, somewhat renegade singer,’ and you know he has pegged him well, for physically, at least, Jennings resembles an outlaw of the old west. But don’t mix him up with those cowboys you used to see in the old movies. He wouldn’t be seen dead in a flamboyantly bejewelled cowboy suit, with a cowboy hat crowning his frame like some cherry, topping an exotic ice cream sundae.

His manner of dress and appearance, with his long hair (only recently tolerated) and his preference for casual wear rather than smart tuxedos have branded him something of a rebel. His sense of rebellion has crossed an infectious breeding ground in which the styles of pop and country could easily merge. But no one can ever question his artistic ability. His voice, rolling and unhurried, is clearly in the image of everything that’s country. Remarkably tender and sensitive are his interpretations of the slower tempo songs. One of his greatest gifts is his ear for a good song, and his recordings of material (by then) relatively unknown writers like Lee Clayton, Kristofferson, Newbury and others, has become something that’s expected of him.

With his solid punchy arrangements he is in a very real way the last of the country/rock singers of the 1950s, owing as much in tradition, to Chuck Berry as to Hank Williams. He finally took leave of the closeted confines of the country music tradition, to which he hardly ever belonged; and turned to being a real man, singing lyrics that he could really get to grips with. Danny O’Keete, one of the writers Jennings latched on to, did a beautiful job with is own Good Time Charlie’s Got The Blues, but Jennings’ has a subdued, inner solution in his version. The harmonica straining mournfully is the music, the chorus is those natural country voices, heavy with grief and resignation.

Jennings’ greatest accomplishment is his album HONKY TONK HEROES, a complete commitment to cowboy music. The songs, all bar one, are by Billy Joe Shaver, a 1970s Texas cowboy, an earthy country philosopher. The songs are of the South, dominated by a sense of loss mixed with an acceptance of it all. Jennings is the complete embodiment of the peculiarly Southern virtues of manliness and honest emotions. The songs come on strong, the melodies linger from an age long gone, the lyrics are something that should mean so much to all of us. Jennings reminds me of the very early Tex Ritter with his his delivery—there’s a meanness in his voice, and somehow you believe that he is alright. Like all great artists, his music portrays himself; he stands for a realness. In a time of sophistication, Jennings is simplicity.

Jennings’ greatest accomplishment is his album HONKY TONK HEROES, a complete commitment to cowboy music. The songs, all bar one, are by Billy Joe Shaver, a 1970s Texas cowboy, an earthy country philosopher. The songs are of the South, dominated by a sense of loss mixed with an acceptance of it all. Jennings is the complete embodiment of the peculiarly Southern virtues of manliness and honest emotions. The songs come on strong, the melodies linger from an age long gone, the lyrics are something that should mean so much to all of us. Jennings reminds me of the very early Tex Ritter with his his delivery—there’s a meanness in his voice, and somehow you believe that he is alright. Like all great artists, his music portrays himself; he stands for a realness. In a time of sophistication, Jennings is simplicity.

Backing Jennings up there is a host of talented writers who are all receiving due recognition, both for their thoughtful songs, and their own recordings. The most famous Texas writer of modern times is Willie Nelson, a man who has been around a long, long time, without ever receiving the commercial success he deserved. Down in Texas he is a hero—even though he is not a big star, his talent as a writer and performer is truly recognised. He possesses a voice you either love or hate—clear as a bell, but sharp as a razor. He writes brilliantly and accurately. His great songs are destined to live on forever, the trouble with Willie is that he’s always been too far in front of the pack to pick up the praise and the awards. He was a singer-songwriter years before it was the thing to do, you could say he unlocked the doors into Nashville for lesser talents like Kristofferson and Newbury, who have reaped huge awards from Nelson’s pioneering spirit. He has now vacated Nashville for the freedom of Texas, and has begun building on a new career which allows him to write and sing in his own way. The new-found freedom emerges strongly on his debut album for Atlantic, SHOTGUN WILLIE, with a masterpiece of a song, Sad Songs And Waltzes (Are Not In This Year)—the one song that really sums up the irony of the Willie Nelson career.

Younger writers have been able to build on Nelson’s experiences, and though Billy Joe Shaver is no overnight success, he has found acceptance more readily accorded on Nashville than he would have done 14 years ago. The deep-thinking, far-sighted Bobby Bare believed in Billy Joe right from the first time he heard him. Influenced by Jimmie Rodgers, he writes in a real, earthy, basic country style. His debut album is another gem that fits easily into the contemporary cowboy scene. OLD FIVE AND DIMMERS LIKE ME is everything that good country music should be—honest and real. The songs that Jennnings picked up for his HONKY TONK HEROES album from the Shaver pen have got that rolling ‘western’ feel about them. The title song starts off slowly, with acoustic guitar work and a vocal from Waylon that smacks of the feel that the legendary Marc Williams had on his brilliant recordings of the early 1930s. Omaha is a typical trail song—it comes on strong and immediately conjures up visions of a dirty, mean cowboy reminiscing about home. Ride Me Down Easy is a lolloping ranch song, it has much more of a western feel in Jennings hands than the original cut by Bobby Bare. Billy Joe Shaver is a natural cowboy writer of real images and lines that you could never predict—Waylon Jennings is the best damn cowboy around to paint those images into pictures.

There are many more young cowboys who grew up in Texas and headed for Nashville hoping for fame and fortune. Some were lucky and made it, but the success never happened. Johnny Bush has long been associated with Willie Nelson, but now he’s making his way in contemporary country music under his own steam. Unlike so many other country singers, Johnny’s a city boy, born in Houston. He’s played almost every joint and barroom in Texas, just drifting from place to place, job to job. But now he’s really beginning to make a name for himself. He lives in Texas still and thrives on being around cowboy and rodeo people. Mind you with his dark tan and cowboy hat, Johnny looks just a little like a cowboy himself. Gene Thomas is more of a songwriter than a singer, and I guess if he never writes another song, no one could ever forget his Lay It Down, easily the best contemporary country song of the 1970s not to have made the charts. Thomas has had quite a long career in the music business being part of a double act down in Houston, but it’s as a Nashville songwriter in the contemporary vein that he is really making his mark.

The most unusual cowboy of all in modern sense must be Kinky Friedman, a protégé of the Glaser Brothers, a trio who hail from Omaha, emerged in the 1960s as the top country harmony group, and have now split to go their separate ways, but are held together by their business ties. Kinky leads the first Jewish-Texas-long-haired country band. The band is a ‘solid’ country and western outfit even by Nashville standards with fiddle, steel and acoustic guitars providing the background to Friedman’s basic Texas vocals. With his ten-gallon hat, pearl-buttoned velvet shirt, tinted glasses and cowboy boots with embroidered Gold Stars of David he must look quite a sight, but there’s no doubt his influences are country all the way. His debut album, SOLD AMERICAN, produced by Chuck Glaser, with Jim and Tompall assisting on background vocals features The Nashville Studio Band augmented by Norman Blake, Jimmy Payne, David Briggs, Buddy Spicher and other notable Music City pickers. Although a few of the songs may offend the more conservative listener, as a writer Kinky has a great future with Western Union Wire, Silver Eagle Express, High On Jesus and Sold American coming over as really strong country tunes.

The most unusual cowboy of all in modern sense must be Kinky Friedman, a protégé of the Glaser Brothers, a trio who hail from Omaha, emerged in the 1960s as the top country harmony group, and have now split to go their separate ways, but are held together by their business ties. Kinky leads the first Jewish-Texas-long-haired country band. The band is a ‘solid’ country and western outfit even by Nashville standards with fiddle, steel and acoustic guitars providing the background to Friedman’s basic Texas vocals. With his ten-gallon hat, pearl-buttoned velvet shirt, tinted glasses and cowboy boots with embroidered Gold Stars of David he must look quite a sight, but there’s no doubt his influences are country all the way. His debut album, SOLD AMERICAN, produced by Chuck Glaser, with Jim and Tompall assisting on background vocals features The Nashville Studio Band augmented by Norman Blake, Jimmy Payne, David Briggs, Buddy Spicher and other notable Music City pickers. Although a few of the songs may offend the more conservative listener, as a writer Kinky has a great future with Western Union Wire, Silver Eagle Express, High On Jesus and Sold American coming over as really strong country tunes.

Not all of the singers and writers that loosely fit into the contemporary cowboy scene hail from Texas. Tompall Glaser, though not quite so deeply involved in the scene as some of the others, nevertheless grew up on a diet of cowboy music and has progressed from writing picturesque cowboy ballads for Marty Robbins to more personal lyrics like Charlie, Barred From Every Honky Tonk In Town and Bad, Bad Cowboy. I feel that Tompall is destined for a very successful solo career, but it’s possible that the average country fan may neglect his new-found freedom, and he will find, like Waylon Jennings, Willie Nelson and Kristofferson, that he is appealing more to a ‘rock’ audience than he ever dreamt possible.

Hoyt Axton, a big, burly brawler of a man was born in the mid-west into a solidly musical family. His mother, Mae Boren Axton, worked for the Opry and as press representative for artistes like Jim Reeves, Hank Snow and Elvis Presley. She was also responsible for several country songs of the 1950s, including Presley’s Heartbreak Hotel. Hoyt himself has written some fine songs—Joy To The World, Greenback Dollar and Never Been To Spain. Some of them are funny, others painful, but he has the same ironic attitude towards all of them. He has a terrific voice—powerful, warm and full-throated, occasionally dropping down to a bear-like growl to get the full feelings from his songs.

There’s a backwoods feel about his music, he conveys a good-timey ‘Sprit of America’ atmosphere. His melodies are not particularly interesting and his lyrics are certainly not outstanding, but they do have broadness of conviction and the sturdiness of a redwood tree. He just has to be one hundred per cent proof—the sense of tradition throughout his music is obviously strong. He’s definitely country-based, but with more than the average share of funkiness. Joy To The World has a happy-go-lucky freewheeling air and Never Been To Spain has a hoe-down feeling with an easy honky-tonk piano giving way to an admirable guitar break. A folk figure of some renown in the early 1960s, Hoyt Axton has come on in the 1970s as some kind of cult figure in contemporary country music circles.

So many of the new breed of country singers are ignored by country fans and it’s a crying shame. Jonathan Edwards came out with two beautiful albums a couple of years ago, and no self-respecting fan should miss his version of Honky Tonk Stardust Cowboy. It’s a song all about some down-and-out who regularly gets all dressed up in cowboy boots, a rhinestone suit and a Stetson, gets drunk, hangs around sleazy bars singing old cowboy songs. Jonathan has a lovely, light, high voice and sings the unstartling song in a unstartling way, but with Bill Keith’s steel weaving in and around the vocal, the overall feel is quite startling.

Another contemporary singer who’s been given the cold shoulder by most country music lovers is the brilliantly talented John Stewart. He sounds as if he’s lived, and so he has. With his cosy, wistfully sheltered songwriting style about places and hopes and dreams and people, Stewart’s pathos hasn’t quite been commercially accepted. His songs littered with place names; he seems obsessed with travel and the intangibility of some aspects of modern living: Arkansas Breakout from his SUNSTORM album spells out the predicament of self-determination for people in an urban society.

Being a melancholic 33-year-old who has seen life, Stewart writes songs of despair tinged with hope. A superb acoustic guitarist, he sings rugged songs of the open road. Melodically he’s no lightweight and the heavily covered July, You’re A Woman is a superb testimony to John’s capabilities as a clever lyricist whose music perfectly suits the melancholia of the song. His splendidly fertile mind has been responsible for some of the most exhilarating listening pleasure that I’ve enjoyed over the past three or four years and his five albums, CALIFORNIA BLOODLINES, WILLARD, THE LONESOME PICKER RIDES AGAIN, SUNSTORM and CANNONS IN THE RAIN are easily the finest contemporary albums of the 1970s standing head and shoulders above anything else that’s been released.

California has always been a magnet for budding musicians and there’s a thriving country music scene there that encompasses all that’s good in contemporary cowboy music, but owing little to Nashville or Bakersfield. Undoubtedly the leaders of the scene there must be The Eagles, a band that’s been together for little more than two years, yet achieved a sound and togetherness that dwarfs all of those around them. They are possibly the most resilient and flexible band I’ve heard. Their songs range from light cowboy sketches to heavy soulful statements, and some of the harmonies produced between Bernie Leadon on lead guitar or banjo and Glen Frey on Dobro are magic. They have a semblance or originality based on their songwriting ability, and it all came together on their second album DESPERADOS released in the middle of 1973.

On one side it deals with the story of the Doolin’ Dalton gang—outlaws from Kansas in the 1890s, but further draws the parallel between the life styles of outlaws with that of travelling musicians of the day. Just witness the brilliance of Outlaw Man (Band), which really underlines the way in which contemporary musicians can identify themselves with the cowboy way of life in the last century. The time both for outlaws and musicians is short in both the same way—because you can’t go through till you’re past 40 and be living the same way.

Even down to their attire, with the faded Levis and sweat shirts, the band leaves no one in any doubt that they are dudes from out of California. They’re a fine band who present their songs in a most appealing manner, decorating them with diverse natural harmonies and some equally effective instrumental backing. Yeah! They are really loose and laid back and mellow, and whenever I hear the wistful Tequila Sunrise, I’m tempted to think I ought to take a swig straight from the bottle. The album is a lovely breath of country air, a delight from start to finish.

Over notable ‘West Coast’ groups which are involved on the fringe of country music include the multi-talented Nitty Gritty Band, but they are more involved in merging the traditional sounds of country music with upbeat rock’n’roll. Commander Cody and The Lost Planet Airman favour the old rock’n’roll and boogie woogie sounds, and only have a passing flirtation with cowboy songs, whereas The New Riders of the Purple Sage, as the name implies are solidly into cowboy music. They are not a bunch of sad young pseudo-electric cowboys endeavouring to cash in on a current trend, but a logical extension of American country music. Their first album quickly established their sound—the music’s tight and falls into a straight country bag with plenty of steel guitar swirling around the vocal harmonies. Glendale Train is a song about a train robbery, while Portland Woman portrays life on the road for rock’s contemporary cowboys. Their strongpoint is obviously harmonies, but never overlook their instrumentation, which is always striving for individuality without losing the natural feel of the music. It’s difficult to say just how authentic this West Coast country music is, for like all forms of music, traditions have to change to meet the tradition.

Over notable ‘West Coast’ groups which are involved on the fringe of country music include the multi-talented Nitty Gritty Band, but they are more involved in merging the traditional sounds of country music with upbeat rock’n’roll. Commander Cody and The Lost Planet Airman favour the old rock’n’roll and boogie woogie sounds, and only have a passing flirtation with cowboy songs, whereas The New Riders of the Purple Sage, as the name implies are solidly into cowboy music. They are not a bunch of sad young pseudo-electric cowboys endeavouring to cash in on a current trend, but a logical extension of American country music. Their first album quickly established their sound—the music’s tight and falls into a straight country bag with plenty of steel guitar swirling around the vocal harmonies. Glendale Train is a song about a train robbery, while Portland Woman portrays life on the road for rock’s contemporary cowboys. Their strongpoint is obviously harmonies, but never overlook their instrumentation, which is always striving for individuality without losing the natural feel of the music. It’s difficult to say just how authentic this West Coast country music is, for like all forms of music, traditions have to change to meet the tradition.

Rather surprisingly there’s even an offshoot of cowboy music on the East Coast in New York. The steel guitar played in a lazy laid-back country fashion has become quite popular in the New York studios and much of the music emitted from there has even rivalled Nashville for its freshness. Typical of the New York cowboys is Chip Taylor, tall and fair-haired, he goes around in cowboy boots, a cowboy shirt and faded denims—right slap bang in the middle of New York where he lives and works. Chet Atkins once described him as: ‘The only writer in New York who can write country music.’ For most of his career he has primarily been a composer of quite lyrical songs recorded by other artistes like Waylon Jennings who cut Sweet Dream Woman and Bobby Bare who made A Little Bit Later On Down The Line into a country hit.

Rather surprisingly there’s even an offshoot of cowboy music on the East Coast in New York. The steel guitar played in a lazy laid-back country fashion has become quite popular in the New York studios and much of the music emitted from there has even rivalled Nashville for its freshness. Typical of the New York cowboys is Chip Taylor, tall and fair-haired, he goes around in cowboy boots, a cowboy shirt and faded denims—right slap bang in the middle of New York where he lives and works. Chet Atkins once described him as: ‘The only writer in New York who can write country music.’ For most of his career he has primarily been a composer of quite lyrical songs recorded by other artistes like Waylon Jennings who cut Sweet Dream Woman and Bobby Bare who made A Little Bit Later On Down The Line into a country hit.

He got turned onto country music by listening to radio programmes as a youngster and has never ceased to be interested in the music since. By the time he was 16 he was singing and playing guitar in a local country group called The Town and Country Brothers. A couple of years later he joined the King Label down in Cincinnati as a writer and session musician. This was followed by a short period in Nashville with MGM before returning to New York as a pop writer and producer. He enjoyed some notable success with The Troggs and the controversial Wild Thing and The Hollies with I Can’t Let Go. Later he began recording with two fellow New York producers, Trade Martin and Al Gorgoni and the trio cut several beautiful laid back albums with GOTTA GET BACK TO CISCO containing some quite outstanding material. This was followed last year by Chip’s own solo album, GASOLINE, the title track being a snappy country tune with a catchy lyric that could do well when picked up by a Nashville singer. Though Taylor has not been a commercial success with his own recordings, his influence as a writer has been felt in Nashville, and once again it’s forward-looking people like Jennings and Bobby Bare who have realised the potential of his songs.

He got turned onto country music by listening to radio programmes as a youngster and has never ceased to be interested in the music since. By the time he was 16 he was singing and playing guitar in a local country group called The Town and Country Brothers. A couple of years later he joined the King Label down in Cincinnati as a writer and session musician. This was followed by a short period in Nashville with MGM before returning to New York as a pop writer and producer. He enjoyed some notable success with The Troggs and the controversial Wild Thing and The Hollies with I Can’t Let Go. Later he began recording with two fellow New York producers, Trade Martin and Al Gorgoni and the trio cut several beautiful laid back albums with GOTTA GET BACK TO CISCO containing some quite outstanding material. This was followed last year by Chip’s own solo album, GASOLINE, the title track being a snappy country tune with a catchy lyric that could do well when picked up by a Nashville singer. Though Taylor has not been a commercial success with his own recordings, his influence as a writer has been felt in Nashville, and once again it’s forward-looking people like Jennings and Bobby Bare who have realised the potential of his songs.

I’ve always been surprised by the lack of acceptance for John Denver in country music. Though he has a voice that’s just a bit too pure and unemotional for some people. I think that on a song like Rocky Mountain High—Colorado, the mountains, the fresh clean air—it’s just right. It really encompasses everything Denver’s about, it’s a beautifully cut, uncluttered track. His name is familiar to many people, but it’s more through other people’s occasional coverage of his songs than his own versions. Although he now lives out of Denver in Colorado, John has been raised in the city and much of his material is really about his own love of a certain freedom based around a country existence opposed to a town trap. He is one of the most successful purveyor of contemporary country music in the States and during the past few years with material like I’d Rather Be A Cowboy and Take Me Home Country Roads, he has incorporated a really strong country influence with steel guitar, banjo, fiddle, Dobro and autoharp creeping into his recordings behind the usual strongly played acoustic guitars.

With an article of such a wide scope as this I make no apologies for omissions—sure I could have included Kristofferson, John Prine, Jesse Winchester, Steve Goodman, Troy Seals, Red Lane and a host of others, but I feel that though they all helped in the new cowboy scene, none have had such a profound influence as the ones I have actually mentioned in depth. Although the contemporary cowboy scene has sprung up overnight, the denim-clad writers and singers are fast changing the face of county music and finding an ever-wider audience. They are not turning their backs on their elders who made country music so great—they owe their livelihood to the Ritters and Acuffs and most of these newer artistes love and have a great feeling for the old music. It was those singers who blazed the trail for the youngsters to follow, now they are expanding the music and bringing it into perspective in the 1970s. They are not renegades, but an important and integral part of country music—for my money they have more authenticity than the string-filled, mass-produced country music that sprung up in the early 1960s and almost submerged country music as a separate identifiable form of music.

Cowboy Music is not dead! It’s alive and kicking, but perhaps not easily recognised by those who were brought up on the idea that cowboy music is all about horses, Tex Ritter, Gene Autry and Roy Rogers. There’s a new type of cowboy music, it deals with the 1970s but the basic freedom and romantic air that abounded in the songs of the cowboy of yesterday is all there today.

You cannot really pick a leader of the cowboy scene today, just like in the past, it has emerged in several centres, but has come together as an entirely separate entity of country music. As a natural extension of the old cowboy scene, it’s perfect, but don’t expect the lyrics or sounds to be quite the same. In order for the music to exist in the 1970s it had to be current and acceptable—people like Waylon Jennings, The Eagles, Billy Joe Shaver, Willie Nelson, The New Riders of the Purple Sage, John Stewart and others are the ones who are laying down the songs and the styles. All of them in their own way are re-enacting the golden days of cowboy music.

Many of the contemporary cowboys hail from Texas. Like Waylon Jennings—a man who has lived—there is a suffering on his face, not the drooping miserable look of a failure. No, his face, chipped and worn about the eyes and cheekbones, is a result of a life being knocked down repeatedly, not so much physically, but more of the outward expressions of internal weariness. On the sleeve notes of his album LADIES LOVE OUTLAW, Robert Hilburn calls Jennings ‘A ragged, exciting, somewhat renegade singer,’ and you know he has pegged him well, for physically, at least, Jennings resembles an outlaw of the old west. But don’t mix him up with those cowboys you used to see in the old movies. He wouldn’t be seen dead in a flamboyantly bejewelled cowboy suit, with a cowboy hat crowning his frame like some cherry, topping an exotic ice cream sundae.

His manner of dress and appearance, with his long hair (only recently tolerated) and his preference for casual wear rather than smart tuxedos have branded him something of a rebel. His sense of rebellion has crossed an infectious breeding ground in which the styles of pop and country could easily merge. But no one can ever question his artistic ability. His voice, rolling and unhurried, is clearly in the image of everything that’s country. Remarkably tender and sensitive are his interpretations of the slower tempo songs. One of his greatest gifts is his ear for a good song, and his recordings of material (by then) relatively unknown writers like Lee Clayton, Kristofferson, Newbury and others, has become something that’s expected of him.

With his solid punchy arrangements he is in a very real way the last of the country/rock singers of the 1950s, owing as much in tradition, to Chuck Berry as to Hank Williams. He finally took leave of the closeted confines of the country music tradition, to which he hardly ever belonged; and turned to being a real man, singing lyrics that he could really get to grips with. Danny O’Keete, one of the writers Jennings latched on to, did a beautiful job with is own Good Time Charlie’s Got The Blues, but Jennings’ has a subdued, inner solution in his version. The harmonica straining mournfully is the music, the chorus is those natural country voices, heavy with grief and resignation.

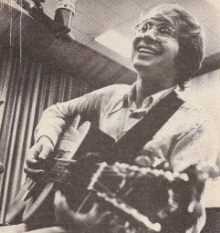

Willie Nelson - sharp as a razor

Backing Jennings up there is a host of talented writers who are all receiving due recognition, both for their thoughtful songs, and their own recordings. The most famous Texas writer of modern times is Willie Nelson, a man who has been around a long, long time, without ever receiving the commercial success he deserved. Down in Texas he is a hero—even though he is not a big star, his talent as a writer and performer is truly recognised. He possesses a voice you either love or hate—clear as a bell, but sharp as a razor. He writes brilliantly and accurately. His great songs are destined to live on forever, the trouble with Willie is that he’s always been too far in front of the pack to pick up the praise and the awards. He was a singer-songwriter years before it was the thing to do, you could say he unlocked the doors into Nashville for lesser talents like Kristofferson and Newbury, who have reaped huge awards from Nelson’s pioneering spirit. He has now vacated Nashville for the freedom of Texas, and has begun building on a new career which allows him to write and sing in his own way. The new-found freedom emerges strongly on his debut album for Atlantic, SHOTGUN WILLIE, with a masterpiece of a song, Sad Songs And Waltzes (Are Not In This Year)—the one song that really sums up the irony of the Willie Nelson career.

Younger writers have been able to build on Nelson’s experiences, and though Billy Joe Shaver is no overnight success, he has found acceptance more readily accorded on Nashville than he would have done 14 years ago. The deep-thinking, far-sighted Bobby Bare believed in Billy Joe right from the first time he heard him. Influenced by Jimmie Rodgers, he writes in a real, earthy, basic country style. His debut album is another gem that fits easily into the contemporary cowboy scene. OLD FIVE AND DIMMERS LIKE ME is everything that good country music should be—honest and real. The songs that Jennnings picked up for his HONKY TONK HEROES album from the Shaver pen have got that rolling ‘western’ feel about them. The title song starts off slowly, with acoustic guitar work and a vocal from Waylon that smacks of the feel that the legendary Marc Williams had on his brilliant recordings of the early 1930s. Omaha is a typical trail song—it comes on strong and immediately conjures up visions of a dirty, mean cowboy reminiscing about home. Ride Me Down Easy is a lolloping ranch song, it has much more of a western feel in Jennings hands than the original cut by Bobby Bare. Billy Joe Shaver is a natural cowboy writer of real images and lines that you could never predict—Waylon Jennings is the best damn cowboy around to paint those images into pictures.

There are many more young cowboys who grew up in Texas and headed for Nashville hoping for fame and fortune. Some were lucky and made it, but the success never happened. Johnny Bush has long been associated with Willie Nelson, but now he’s making his way in contemporary country music under his own steam. Unlike so many other country singers, Johnny’s a city boy, born in Houston. He’s played almost every joint and barroom in Texas, just drifting from place to place, job to job. But now he’s really beginning to make a name for himself. He lives in Texas still and thrives on being around cowboy and rodeo people. Mind you with his dark tan and cowboy hat, Johnny looks just a little like a cowboy himself. Gene Thomas is more of a songwriter than a singer, and I guess if he never writes another song, no one could ever forget his Lay It Down, easily the best contemporary country song of the 1970s not to have made the charts. Thomas has had quite a long career in the music business being part of a double act down in Houston, but it’s as a Nashville songwriter in the contemporary vein that he is really making his mark.

Kinky Friedman

Not all of the singers and writers that loosely fit into the contemporary cowboy scene hail from Texas. Tompall Glaser, though not quite so deeply involved in the scene as some of the others, nevertheless grew up on a diet of cowboy music and has progressed from writing picturesque cowboy ballads for Marty Robbins to more personal lyrics like Charlie, Barred From Every Honky Tonk In Town and Bad, Bad Cowboy. I feel that Tompall is destined for a very successful solo career, but it’s possible that the average country fan may neglect his new-found freedom, and he will find, like Waylon Jennings, Willie Nelson and Kristofferson, that he is appealing more to a ‘rock’ audience than he ever dreamt possible.

Hoyt Axton, a big, burly brawler of a man was born in the mid-west into a solidly musical family. His mother, Mae Boren Axton, worked for the Opry and as press representative for artistes like Jim Reeves, Hank Snow and Elvis Presley. She was also responsible for several country songs of the 1950s, including Presley’s Heartbreak Hotel. Hoyt himself has written some fine songs—Joy To The World, Greenback Dollar and Never Been To Spain. Some of them are funny, others painful, but he has the same ironic attitude towards all of them. He has a terrific voice—powerful, warm and full-throated, occasionally dropping down to a bear-like growl to get the full feelings from his songs.

There’s a backwoods feel about his music, he conveys a good-timey ‘Sprit of America’ atmosphere. His melodies are not particularly interesting and his lyrics are certainly not outstanding, but they do have broadness of conviction and the sturdiness of a redwood tree. He just has to be one hundred per cent proof—the sense of tradition throughout his music is obviously strong. He’s definitely country-based, but with more than the average share of funkiness. Joy To The World has a happy-go-lucky freewheeling air and Never Been To Spain has a hoe-down feeling with an easy honky-tonk piano giving way to an admirable guitar break. A folk figure of some renown in the early 1960s, Hoyt Axton has come on in the 1970s as some kind of cult figure in contemporary country music circles.

So many of the new breed of country singers are ignored by country fans and it’s a crying shame. Jonathan Edwards came out with two beautiful albums a couple of years ago, and no self-respecting fan should miss his version of Honky Tonk Stardust Cowboy. It’s a song all about some down-and-out who regularly gets all dressed up in cowboy boots, a rhinestone suit and a Stetson, gets drunk, hangs around sleazy bars singing old cowboy songs. Jonathan has a lovely, light, high voice and sings the unstartling song in a unstartling way, but with Bill Keith’s steel weaving in and around the vocal, the overall feel is quite startling.

Another contemporary singer who’s been given the cold shoulder by most country music lovers is the brilliantly talented John Stewart. He sounds as if he’s lived, and so he has. With his cosy, wistfully sheltered songwriting style about places and hopes and dreams and people, Stewart’s pathos hasn’t quite been commercially accepted. His songs littered with place names; he seems obsessed with travel and the intangibility of some aspects of modern living: Arkansas Breakout from his SUNSTORM album spells out the predicament of self-determination for people in an urban society.

Being a melancholic 33-year-old who has seen life, Stewart writes songs of despair tinged with hope. A superb acoustic guitarist, he sings rugged songs of the open road. Melodically he’s no lightweight and the heavily covered July, You’re A Woman is a superb testimony to John’s capabilities as a clever lyricist whose music perfectly suits the melancholia of the song. His splendidly fertile mind has been responsible for some of the most exhilarating listening pleasure that I’ve enjoyed over the past three or four years and his five albums, CALIFORNIA BLOODLINES, WILLARD, THE LONESOME PICKER RIDES AGAIN, SUNSTORM and CANNONS IN THE RAIN are easily the finest contemporary albums of the 1970s standing head and shoulders above anything else that’s been released.

California has always been a magnet for budding musicians and there’s a thriving country music scene there that encompasses all that’s good in contemporary cowboy music, but owing little to Nashville or Bakersfield. Undoubtedly the leaders of the scene there must be The Eagles, a band that’s been together for little more than two years, yet achieved a sound and togetherness that dwarfs all of those around them. They are possibly the most resilient and flexible band I’ve heard. Their songs range from light cowboy sketches to heavy soulful statements, and some of the harmonies produced between Bernie Leadon on lead guitar or banjo and Glen Frey on Dobro are magic. They have a semblance or originality based on their songwriting ability, and it all came together on their second album DESPERADOS released in the middle of 1973.

On one side it deals with the story of the Doolin’ Dalton gang—outlaws from Kansas in the 1890s, but further draws the parallel between the life styles of outlaws with that of travelling musicians of the day. Just witness the brilliance of Outlaw Man (Band), which really underlines the way in which contemporary musicians can identify themselves with the cowboy way of life in the last century. The time both for outlaws and musicians is short in both the same way—because you can’t go through till you’re past 40 and be living the same way.

Even down to their attire, with the faded Levis and sweat shirts, the band leaves no one in any doubt that they are dudes from out of California. They’re a fine band who present their songs in a most appealing manner, decorating them with diverse natural harmonies and some equally effective instrumental backing. Yeah! They are really loose and laid back and mellow, and whenever I hear the wistful Tequila Sunrise, I’m tempted to think I ought to take a swig straight from the bottle. The album is a lovely breath of country air, a delight from start to finish.

The Eagles

New Riders of the Purple Sage

Bobby Bare

I’ve always been surprised by the lack of acceptance for John Denver in country music. Though he has a voice that’s just a bit too pure and unemotional for some people. I think that on a song like Rocky Mountain High—Colorado, the mountains, the fresh clean air—it’s just right. It really encompasses everything Denver’s about, it’s a beautifully cut, uncluttered track. His name is familiar to many people, but it’s more through other people’s occasional coverage of his songs than his own versions. Although he now lives out of Denver in Colorado, John has been raised in the city and much of his material is really about his own love of a certain freedom based around a country existence opposed to a town trap. He is one of the most successful purveyor of contemporary country music in the States and during the past few years with material like I’d Rather Be A Cowboy and Take Me Home Country Roads, he has incorporated a really strong country influence with steel guitar, banjo, fiddle, Dobro and autoharp creeping into his recordings behind the usual strongly played acoustic guitars.

John Denver

With an article of such a wide scope as this I make no apologies for omissions—sure I could have included Kristofferson, John Prine, Jesse Winchester, Steve Goodman, Troy Seals, Red Lane and a host of others, but I feel that though they all helped in the new cowboy scene, none have had such a profound influence as the ones I have actually mentioned in depth. Although the contemporary cowboy scene has sprung up overnight, the denim-clad writers and singers are fast changing the face of county music and finding an ever-wider audience. They are not turning their backs on their elders who made country music so great—they owe their livelihood to the Ritters and Acuffs and most of these newer artistes love and have a great feeling for the old music. It was those singers who blazed the trail for the youngsters to follow, now they are expanding the music and bringing it into perspective in the 1970s. They are not renegades, but an important and integral part of country music—for my money they have more authenticity than the string-filled, mass-produced country music that sprung up in the early 1960s and almost submerged country music as a separate identifiable form of music.